The whole collection of the previous Essays was meant to be a thematical, and consequently not a historical exposition of a THEORY OF BEING. The next series of Essays is partly historical, i.e. it will consider classical texts on that subject matter, but not without critical annotations from the viewpoint of modern ideas, especially those from Natural Science.

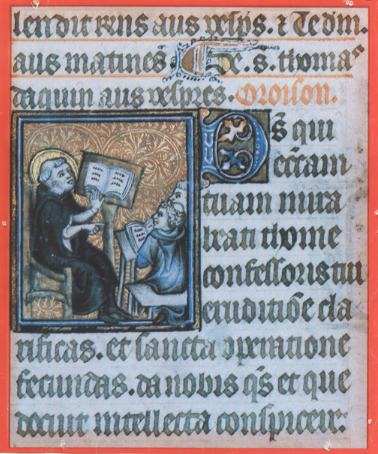

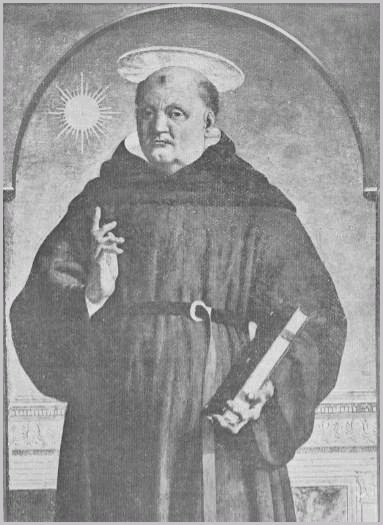

Concerning the classical texts I have in mind those of St Thomas Aquinas (born in 1225 or 1226, died in 1274). He is undoubtedly the greatest metaphysician, but relied very much on the ideas of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (born in 384 or 383, died in 322 or 321 before Christ). The works of St Thomas are for the very most part theological in nature. But he wanted to rationalize Christian Theology, and because Christian Theology is about the World as created (by the divine Creator), the very existence, the being , of that World, and the things in it, was its most important topic. So for the rationalization of Theology a theory of Being was needed. There were already several theories at hand, but St Thomas was looking for one that should, besides on Logic and Language, rely heavily on sense observation. He found it in Aristotle's Metaphysics, which had just become available, initially via Arabic mediators. St Thomas wrote a large Commentary on Aristotle's Metaphysics in which he expounds many ideas concerning the theory of Being. Those ideas permeated through all his other works. For us the most important of these other works are -- among others -- his Summa Theologia, especially the First Part, and his small but important treatise called De Ente et Essentia (On Being and Essence). We shall read some fragments of those texts. At the following Inernet address you can find an English translation of De Ente et Essentia. In case that site is hard accessable, or not existent anymore, you can get it from my own site by clicking on this local link. It is still worthwile to study this treatise, and a very instructive and well written commentary is provided by BOBIK, J., 1970, Aquinas On Being and Essence, University of Notre Dame Press. The Latin text, with a German translation and notes, is provided by BEERETZ, F. L., Thomas von Aquin, De Ente et Essentia, Das Seiende und das Wesen, Philipp Reclam Jun. Stuttgart.

The term Metaphysics has several meanings. Sometimes it means the study of the mystical (whatever that may be), or (the study of) the immaterial. But its most important meaning is : The study of Being-in-so-far-as-it-is-being, i.e. a theory of Being.  Such a study is trying to uncover the ultimate principles of Being. We can also call it by the name Ontology, which means : the study of Being. On this website we will confine ourselves mainly with the principles of material being. Such principles are for instance UNITY, INDIVIDUALITY, (having an) IDENTITY (Whatness, Essence), MATTER-FORM COMPOSITION, CHANGEABILITY, etc. So a genuine being is based on these principles. Within it we can discriminate between per se features of it, and per accidens features. It concerns a per se and per accidens with respect to the Essence of that particular being. The Essence is the principle by and through which a certain being (i.e. a being, pointed to with the finger) is what it is, i.e. by and through which it has its very Identity or Whatness. Every feature that is not necessarily connected with this Essence is a per accidens feature. If, for example Socrates is tanned by the sun (because it has been a fine summer), then this feature of being tanned is a per accidens feature with respect to Socrates' Essence. In the previous Essays we identified the Essence with the Dynamical Law that generated, or could have generated, that being in question. So Socrates is ontologically interpreted as a dynamical system of interacting elements. Socrates at a particular moment in time represents a state of that dynamical system. The Dynamical Law that governs the succession of system-states is implicit, and resides in certain properties of the constituents of the dynamical system. Some features of a being are necessarily connected with its dynamical law, and thus are per se features, other features are not necessarily connected with that dynamical law and are accordingly per accidens features.

Such a study is trying to uncover the ultimate principles of Being. We can also call it by the name Ontology, which means : the study of Being. On this website we will confine ourselves mainly with the principles of material being. Such principles are for instance UNITY, INDIVIDUALITY, (having an) IDENTITY (Whatness, Essence), MATTER-FORM COMPOSITION, CHANGEABILITY, etc. So a genuine being is based on these principles. Within it we can discriminate between per se features of it, and per accidens features. It concerns a per se and per accidens with respect to the Essence of that particular being. The Essence is the principle by and through which a certain being (i.e. a being, pointed to with the finger) is what it is, i.e. by and through which it has its very Identity or Whatness. Every feature that is not necessarily connected with this Essence is a per accidens feature. If, for example Socrates is tanned by the sun (because it has been a fine summer), then this feature of being tanned is a per accidens feature with respect to Socrates' Essence. In the previous Essays we identified the Essence with the Dynamical Law that generated, or could have generated, that being in question. So Socrates is ontologically interpreted as a dynamical system of interacting elements. Socrates at a particular moment in time represents a state of that dynamical system. The Dynamical Law that governs the succession of system-states is implicit, and resides in certain properties of the constituents of the dynamical system. Some features of a being are necessarily connected with its dynamical law, and thus are per se features, other features are not necessarily connected with that dynamical law and are accordingly per accidens features.

The ancient Metaphysicians relied much on the structure of language, especially its subject-predicate structure, like for instance in sentences like :

Here the subject is Socrates, and tanned is the predicate (s.str.), while the term is represents the so called copula, it connects the predicate with the subject, by affirming the being of a certain condition, namely tanned, in or on the subject. In this case tanned is a per accidens determination of the subject (Socrates). Furthermore it is clear that TANNED cannot in principle (i.e. ontologically) exist on its own. It needs a substrate to exist in. This substrate is expressed by the subject-term of the sentence. So the term TANNED presupposes a subject, and this subject signifies a substrate. The substrate (with determinations) can exist on its own, it does not need any other substrate to exist in, that's why it is called Substance (Substantia, meaning that what underlies -- stands under -- the determinations like tanned, and what itself is in no need of a substrate of its own). In this way the structure of a sentence seems to reveal a certain ontological state of affairs.

It could seem that going along such lines ends up with a confusion of Logic and Metaphysics, but things are not that simple. Our language undoubtedly codifies some basic, i.e. fundamental, experience concerning the material world. These primary experiences are somehow brought into the basic structure of language. So language could indeed provide us with some clues about the fundamental ontological structure of reality. This structure is a certain common framework, permeating all beings, and causing them to be beings in the first place. But of course there still remains a difference between Logic and Metaphysics. Logic presupposes Metaphysics, so Metaphysics is more fundamental than Logic.

The texts that we will analyse were written in the thirteenth century. At that time there was in fact no such thing as Natural Science. There existed very little knowledge about material things and processes. This is because to erect a theory about material things one needs data, obtained by sense-observation. But, when we look around in our material world, we find almost an infinity of possible data. The point is that one must know which data are relevant and which are not. But for this one needs theory. It is because this chicken-egg problem that Natural Science made a slow start. Another reason for the virtual absence of Natural Science at those times is that the interest was mainly focussed on theological issues like : The relation of Man with his Creator, the attributes of the Creator himself, and their reflections in the constitution of all his creations. So the ontological investigations of the medieval authors mainly relied on Logic and Language, but were certainly not devoid of reference to sense-observation.

We will follow some texts of St Thomas insofar as they are relevant to our ontological quest, stated in our first Essay of this website : An Essay on Being and Essence . What we will do here is not so much an interpretation of the texts in order to make more clear what the author actually wanted to communicate, but to read relevant parts of the texts in the hope that we still will learn something from them and that we will be further inspired and spurred to do more research about the subject (i.e. about the ontology of beings).

All the texts of St Thomas were written in Latin. Because I assume that not every reader has a knowledge of Latin I shall read them by means of a translation into the English language.

Philosophy is sometimes called a dialogue, not a research program. In a way there is some truth in that. Especially dialogues between thinkers with different backgrounds can be fruitfull for Philosophy, and moreover dialog = social contact. So we want to dialogue as much as possible, wich means that this whole website pretends to be adialogue.

In the next Part we will treat of the conditions that must be satisfied for something to be a SUBSTANCE.