How this works out can best be seen by considering once again the ontology of the individual (See for a treatment of the individual the following Essays :

The Principle of Individuation

What is an Individuum? Part I

What is an Individuum? Part II

What is an Individuum? Part III )

In Thomism the ten Categories (Predicaments), like SUBSTANCE, QUANTITY, QUALITY, RELATION, etc., are interpreted as the ten main types of Being.

So every real being can be subsumed under one of these ten types. However, a type itself, as type, like for instance QUANTITY, cannot be considered as a being. A being must be completely specified. So QUANTITY is not a being, but, according to Thomism, 2.5 cm long is.

[NOTE 1]

Also SUBSTANCE is not a being, only a particular individual Substance is.

Complete specification always implies individuation (and, according to Nominalism only individuals exist, which here means : individual Substances).

To return to Accidents again, any particular individual Accident Thomism considers as (to be) a being, albeit a secondary being, i.e. a non-subsistent being.

Now if we consider for instance the term QUANTITY, then that term only applies to completely specified quantitative determinations, i.e. (according to Thomism) it only applies to an (i.e. any) individual being insofar as it is subsumed under the type QUANTITY. It does not apply to any individual Substance (According to Nominalism it does, and even exclusively so), and it also doesn’t apply to any individual quality, relation, etc. The same can be said with respect to the other Categories : The term SUBSTANCE does not apply to any individual quantity, it does also not apply to any individual quality, etc. It only applies to an (i.e. any) individual Substance. Also the term, say, QUALITY does not apply to any individual Substance, not to any individual quantity, not to relation, etc., it only applies to an (i.e. any) individual being insofar as it is subsumed under the type QUALITY.

To render all this more clear, let me give some examples, in which - in line with Thomism - individual Accidents are considered as individual beings :

The term QUANTITY can be applied to any individual being (such as) 2.5 cm long ("2.5 cm long " is the name of that being, which is a secondary being). We can legitimately say :

"This 2.5 cm length is (a) Quantity." (Now using the abstract term to isolate the Accident).

The term QUANTITY can also be applied to any individual being 5 cm3 in volume (" 5 cm3 in volume " is the name of that being, which is a secondary being).

But it cannot be applied to any individual being (such as) red (" red " is the name of that being, which is a secondary being, in this case a quality), and it cannot be applied to Socrates, or any other individual human being.

The term QUALITY can be applied to any individual being (such as) red (" red " is again the name of that being, which is a secondary being). We can legitimately say :

" This redness is (a) Quality. " (Now using the abstract term to isolate the Accident).

The term QUALITY can also be applied to any individual being white (" white " is the name of that being, which is a secondary being), but it cannot be applied to any individual being 2.5 cm long (" 2.5 cm long " is again the name of that being, which is a secondary being), and also not to any individual being 5 cm3 in volume (" 5 cm3 in volume " is again the name of that being, which is a secondary being), and also not to any individual human being.

And with respect to Substance :

The term SUBSTANCE (which is, in this context, Second Substance) can be applied to any individual human being, and also to any individual starfish, dog, etc., but it cannot be applied to any individual being 2.5 cm long (" 2.5 cm long " is again the name of that being, which is a secondary being), and also not to any individual being red (" red " is again the name of that being, which is a secondary being). We cannot say : " red is (a) Substance ", neither can we say : " this redness is (a) Substance " (using the abstract term to isolate the Accident), but we can legitimately say : "Socrates is a Substance ".

REMARK : Of course these terms SUBSTANCE, QUANTITY, QUALITY, etc., can also be applied to all the corresponding intermediates, for instance as in the proposition "Color is (a) Quality", but color (as all intermediates) is a subtype -- and thus just a type -- (of being), not a being itself, even not a secondary being, because it is still not completely specified.

But if we consider the term UNITY (in the sense of being-one) then Thomism says that this term can be applied to all beings, and this here means that it can be applied to any individual Substance, as well as to any individual quantity, quality, relation, etc., i.e. to any individual Accident. The same goes for some other terms, namely GOOD (bonum), BEAUTIFUL (pulchrum), a THING (res), SOMETHING (aliquid), TRUE (verum) and of course a BEING (ens). So we legitimately can say :

" Socrates is (a) Unity, is Good ", etc., and especially, " is a Being".

But we can also legitimately say :

" This Redness is (a) Unity, is Good ", etc., and especially, " is a Being ", or

" This 2.5 cm length is (a) Unity, is Good ", etc. and especially, " is a Being ".

So these terms (UNITY, GOOD, etc.) transcend all Categories, hence they are called Transcendentals.

This doctrine of Transcendentals is as such held by Thomism.

It is clear that, say, Quantity can only exist (albeit merely as an ontologically dependent being) if it is completely specified (that is, specified by Nature, i.e. ontologically determined), and the same goes for the other Categories (In the case of Substance, its Essence must be completely specified (ontologically determined) in order for it to exist at all).

But because we - on this website - found out that the unity of (at least) Substances comes in several grades (degrees), implying that a Substance could, in a sense, be many

[NOTE 2]

, this unity must also be completely specified (i.e. its degree should be completely specified) in order to exist in extramental reality. Then, any such unity can be referred to by the term UNITY (in the sense of : " this is (a) unity "). Only in this way every (stronger or weaker expressed) Substance can be subsumed under the term of UNITY.

Because the unity of a Substance is conferred onto its Accidents (i.e. those Accidents participate in the Substance's unity), those Accidents, each for themselves, enjoy (that) unity (too), and this is indeed why the term UNITY is transcendental. It applies to all Categories.

Now, Nominalism holds that the term QUANTITY is also a transcendental term, because, so it says, every real being is quantitatively determined

[NOTE 3].

For Nominalism only individual Substances exist, so " every real being " only refers to individual Substances. So the term QUANTITY can be applied to Socrates, because Socrates is quantitatively determined. And it can be so applied to any individual Substance. We can legitimately say : "Socrates is (a) Quantity " (in the sense of : " Socrates is quantitative "), just like we can say : " Socrates is (a) Unity " (in the sense of : " Socrates is ONE ").

Seen it this way, QUANTITY is indeed a transcendental

[NOTE 4].

But, is it really correct to say : " Socrates is (a) Quantity " (and also : " Socrates is (a) Quality ", etc.), and if so, what does it exactly mean?

When Thomism says : " this 1.70 meter length is (a) Quantity ", this means that this 1.70 meter length is wholly (a) Quantity, and nothing else (The same goes for this redness, being wholly (a) Quality, and nothing else).

When, on the other hand, we say : " Socrates is (a) Quantity ", then we know, to be sure, that Socrates is (a) Quantity, i.e. Socrates is quantitative, but we know also that Socrates is not exclusively (a) Quantity (Socrates is quantitatively determined, but Socrates is also (a) Substance, and he is also qualitatively determined).

So Nominalism cannot in the same way assert that Socrates is (a) Quantity as Thomism asserts that this 1.70 meter length is (a) Quantity. And especially it cannot assert that Socrates is (a) Quantity in the same way as it itself can say that Socrates is (a) Unity, Good, etc., where the terms UNITY, GOOD, BEING, etc. are considered to be equivalent (i.e. mutually convertible) in Nominalism as well as in Thomism. And these terms (UNITY, GOOD, etc.) involve all other determinations when applied to Socrates, while the term QUANTITY does not (Of course, Nominalism could stipulate that it does, but then it introduces an ad hoc element) :

Thomism, on the other hand, does not say that Socrates is a quantity, but only that, for example, 1.70 meter length is a quantity (and also it needs not to say that Socrates is quantitatively determined. It allows for indeterminateness with respect to his quantity).

Thomism, as has been said, applies, say, the term QUANTITY to any individual being that is subsumed under the type (type of being) QUANTITY (again : for example 1.70 meter lenght). In this way it can leave out of consideration the Substance itself (it only involves the Substance itself as soon as it uses the term 1.70 meter long ). So even if there were quantities existing all by themselves it could still apply the term QUANTITY to them.

Not so in Nominalism.

Nominalism always applies the term QUANTITY to one or another individual Substance. It says that every individual Substance is quantified. But it must be specific and definite, using for example the term 2.5 cm long, and then it says : " This crystal is 2.5 cm long ". The concrete term 2.5 cm long of this proposition is (in Nominalism) connotative. It signifies primarily the Substance involved, and secondarily the truth of a certain proposition (So here we do not have a substance + determination (accident), but a substance + a true proposition about that substance). Hence that which is connoted does not refer to something (existing) in Reality. This connoted proposition poses that the conditions, necessary for the attribution of the term 2.5 cm long, are met, based for example on an observation.

When Nominalism uses a general term, this term refers to a multitude of individuals, without thereby presupposing anything in them that they should have in common, or anything that is necessarily exactly repeated across the relevant multitude of individuals. The term refers to this multitude by signifying the individuals in a disjunctive way. For instance the term HUMAN BEING refers either to Socrates, or to Plato, or to Peter, or …. In this way even a general term refers to an individual. The ground (i.e. the legitimacy) for using the general term is the (observable) fact that the relevant individuals happen to look very similar.

The most important point however is the fact that for Nominalism only individual Substances exist in extramental Reality, and nothing else. If it uses the term SOCRATES in the usual way, then it must admit that SOCRATES is in fact a general term, referring disjunctively to each life stadium of the greek philosopher, i.e. to each here-and-now individual (together making up the historical individual Socrates, i.e. the individual Socrates in the usual sense). And these life-stadia only look similar to each other (thereby Nominalism forgets that in many organismic species the individual life-stadia can look very different indeed). So the view of individuality within Nominalism always concerns the here-and-now individual. In Thomism, on the other hand, there is room for a historical individual as well.

Because Nominalism does not admit of a real distinction between Substance and Accident, it denies any Substance-Accident Scheme describing Reality.

HENCE, FOR A JUDGEMENT AND EVALUATION OF THE SUBSTANCE-ACCIDENT SCHEME THE VIEW OF INDIVIDUALITY -- HISTORICAL INDIVIDUAL OR HERE-AND-NOW INDIVIDUAL -- IS CRUCIAL.

Only within a view of the individual as a historical individual the Substance-Accident Scheme makes sense (because a here-and-now individual does not admit of mutual replacements of its accidents), and we shall have to investigate whether such a view of the individual will also hold for the inorganic domain, because in the non-nominalistic scholastic philosophy one distinguishes between Substance and Accident in that domain too.

But let us first address some curious organisms.

Also with respect to other organisms difficulties can be encountered regarding their individuality status. There "to be an individual" seems to come in degrees, because in many lower organisms "the individual" can also be interpreted as a colony of individuals. Such a colony can, if we consider such colonies across a series of species of organisms, show an increasingly stronger degree of individuality.

Investigation of such cases will undoubtedly deepen our insight in the phenomenon of being an individual.

The view of an individual extending between two substantial changes encounters difficulties also in the case of bacteria, which reproduce themselves through division. This division itself could be interpreted as already being a substantial change, despite the fact that the whatness remains the same. Normally a new individual appears when it is created by a substantial change leading from a set of freely existing elements to one whole new being, while it is terminated by a disintegration (which is also a substantial change) of that being. But what about the bacterium? Is the bacterium individuum terminated after it has split in two, or does it remain that same individual, because no change in whatness has occurred?

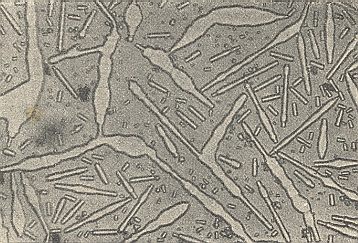

Something like that we see in twin crystals, and also in the case of cleaving a crystal along a plane of weaker chemical bonds.

N.B. Such considerations, which we could call considerations from the perspective of natural philosophy, I miss in philosophical treatises concerning individuality, for example, GRACIA, J., 1988, Individuality

Perhaps "to be an individual" is an analogous concept, i.e. a concept referring primarily to a set of specifically clear and perfect cases (this set is the primary instance), but, secondarily also referring to less perfect cases. In precisely what way would it be analogous? What is the primary instance of being-an-individual? Maybe this is : "to be a person" (We can read about this in St Thomas, Summa Theologiae, 1a, 29, 1c).

Probably the analogous character of "to be an individual" manifests itself in its being gradual, i.e. individuality comes in several degrees. But is this a genuine case of being analogous?

Figure 1. From a seed, a crystal is growing in a solution. After a short time (complete) substitution sets in (dark blue), but ceases later on, after which the crystal grows further, accepting again exclusively atoms of the original species (light blue).

Now we could imagine that at a certain moment in time in the course of the initial crystallization phase, alien, but not too different, atomic species, "impurities", enter the solution in which the growing crystal finds itself, and these atoms are now going to occupy all the next vacant points (locations, places) of the lattice, points that in fact should be occupied by atoms of the original species. All this will indeed happen when at the same time the original atomic species has (temporarily) become exhausted, i.e. when its concentration is, at that time, low, or when it is absent in the solution.

In the case of an Alum crystal, that normally consists of four different atomic species, namely Potassium, Aluminum, Sulfur and Oxygen, it is in this way possible that the places in its crystal lattice, which normally would be occupied by Aluminum atoms, are now, during the continued initial growth phase, being occupied by Chrome atoms, i.e. from now on Chrome atoms instead of Aluminum atoms are being received by the growing crystal, resulting in an outer layer consisting of Potassium atoms, Chrome atoms, Sulfur atoms and Oxygen atoms. Once happened, such a substitution cannot be reversed anymore. The crystal grows by apposition of atoms, the crystal lattice extends itself layer by layer, and, when a layer is covered by a next layer, then nothing can happen to it anymore, as long as the crystal does not dissolve again.

So by the substitution decribed [As would by now be clear, "substitution" here does not mean an actual exchange of atoms, but an occupation of places, that would normally be occupied by the original atomic species.], alien atoms are being accepted by the crystal, and hence the chemical composition of that crystal is different from one in which the substitution had not occurred. In the presently developed crystal the relative contribution of the alien atoms is large, because already shortly after the beginning of the crystallization apposition took place of that other atomic species (in the described case).

But now it could happen (i.e. we could imagine) that during further growth of the crystal this substitution activity is rapidly going to decline, because for example the growth environment -- the solution -- changes again with respect to composition. And suppose that finally this substitution activity totally ceases, while the crystal just continues to grow. And it can continue to grow because (so we imagine) atoms of the original atomic species are again entering the solution (making it again supersaturated with respect to that original species), while the atoms of the alien atomic species are exhausted, all this -- supposing further -- resulting, after a longer period of continued growth, in a large crystal, in which the relevant lattice points in the newly formed layers are again being occupied by atoms of the original atomic species.

The result of all this is that the relative contribution, in the resulting (large) crystal, of the substituting atomic species (the alien species) has now become very small again. Hence we now have to do with in fact a very large molecule, namely the crystal, in which -- so we could describe it -- here and there small chemical changes have taken place in virtue of the initial substitution, in which "chemical changes" here means that we observe a difference in local chemical composition, when compared with a case without any substitution having taken place at all (For the sake of the argument it is moreover legitimate to imagine even an actual exchange of atoms having occured in the crystal lattice, and thus to imagine a chemical change having occurred within the crystal lattice).

We could interpret these changes, having occurred to such a large Whole, just as changes of a certain condition or state of that Whole, i.e. of that crystal (compared with the corresponding state of a crystal in which no substitution had occurred), because, say, the tanning of a human individual by the sun is a small chemical change too (compared with a non-tanned individual), having occurred to a relatively large Whole. And becoming tanned (as being tanned, as having become tanned) is unanimously regarded as a change of state or condition ocurring in a subject that itself remains the same (Socrates-tanned is still Socrates). The Identity (whatness) of that crystal then is the same as that of one in which such substitutions have not taken place, hence a "pure" crystal. Expressed more precisely : the Identity (whatness) of the crystal is again the same as one in which substitution did not occur (again, because earlier in its growth history it wasn't).

So we must conclude that the Identity (whatness) of the crystal has changed DURING ITS GROWTH (in which initially complete substitution took place), because in the beginning the relative contribution of the alien atoms was large, while later on this relative contribution decreases again, it becomes small to very small (like in the very beginning of the substitution process), resulting in the crystal again becoming almost the same (with respect to whatness, i.e. with respect to its specific composition) as a pure crystal.

This change (of Identity) is, it is true, induced by external causes (namely the composition of the growth environment), but this is quite normal for a substantial change (i.e. it is perfectly compatible with substantial change) -- A human being for instance can get killed by a natural catastrophe. So in the beginning of the growing process the crystal's Identity (whatness) was, say A, a little later it became B, and finally it became A again. But this change and rechange occurred to the same individual it seems.

And this change, having occurred during growth of the crystal individual, involuntary calls on a comparison with the metamorphosis taking place in many insect species. Also in this case a chemical change takes place during the growth of the insect individual. Nevertheless we are not inclined to call this a substantial change : we do not end up with a new insect species. The genetic mak-up remains the same before and after metamorphosis. The difference with the change during crystal growth relates undoubtedly to the difference in the way of growing : The crystal grows by apposition (addition of new parts), while an organism generally grows by intussusception (the insertion of new parts into a semi-fluid and consequently deforming Whole).

We ask ourselves whether the view of an individuum as a historical individual is universally valid, for is it also valid for crystal individuals?

REMARK : Recall that we concluded earlier that for a Substance-Accident Metaphysics to make sense, the concept of individuality should refer to a historic individuum, i.e. the total sequence of states that a substance passes through. This is easy to conceive of in the case of organisms (including man), but is it also so easy in the case of inorganic beings?

The reason why we should interpret the metamorphosis in insects as just a change in their condition is that we take the Identity (whatness) of the insect individual to remain the same despite the very radical internal and external chemical and morphological reconstruction of the insect, thus despite the fact that we are inclined to interpret this as a substantial change (versus an accidental change). Peculiar is that this change of condition has intrinsic causes : It occurs in every individual of the relevant insect species, and moreover in the same way. This is because "the necessity to metamorphosize" is a generic proprium (always present in all the individuals of a certain 'genus' of insects). Surely this contrasts with the relevant events in crystals. The described substantial change has in the latter purely external causes. The crystal individuals of the crystal species concerned do not have to undergo such changes necessarily (i.e. their very essence does not demand such changes).

In the whole context of the described growth of the crystal the expounded change in it is per accidens, also when the change itself can be interpreted as a substantial change. The growth environment just happened to change, and this external factor (external in relation to the crystal) caused the substitution to occur, but the change turned out to lead to a (for the time being) different chemical composition (not just an impurity), which could be interpreted as a substantial change, i.e. a change of the crystal's Identity or whatness (later, in our experiment, the original Identity was recovered, after a prolonged growth involving the original atomic species again). In the case of the described crystal there is a substantial difference between the first growth phase (with -- during its, say, latter half -- complete substitution) and the final phase which is the result of a prolonged subsequent growth without substitution. This difference can come about in a continuous way. At the atomic level it is of course not continuous.

If we view the individual, in the case of that crystal, as a historical individual, hence analogously to a human individual, but also to an insect individual (undergoing metamorphosis), then we arrive at the peculiar conclusion that this individual underwent a substantial change during its existence. But this is, so expressed, impossible, because a historical individual remains that same individual, even under changes, changes which consequently should be interpreted as accidental : I cannot become somebody else, much as I would like to. Hence something must be wrong, either with the view of individuality used with regard to the described crystal, or with the view of that change as a substantial change.

Let us check up both. Of course they relate to one another.

The change in chemical composition would, for example in the case of Alum, when, in it, Aluminum is substituted by Chromium, boil down to the difference between Potassium Aluminum Sulfate ( = ordinary Alum, Potash Alum) and Potassium Chromium Sulfate ( = Chrome Alum), and these are two different chemical compounds, which, also in modern Scholastics ( = Neothomism ), are interpreted as two different Substances (in the metaphysical sense). Hence the change ( when we imagine such a substitution as an actual exchange between Aluminum and Chromium in one and the same crystal) is a substantial change anyway.

But does such a substantial change represent a change of one and the same individual? No, it cannot be so, as we established earlier. Hence, it seems that the view of individuality, as applied to the crystal, is false : We cannot view the crystal individual as a historical individual. We should instead view this individual as a here-and-now individual. But then a Substance-Accident Structure becomes irrelevant with regard to it (and to all crystals), because in that case all determinations (of it) are transcendental (NOTE 6). This here-and-now individual becomes -- during growth -- another Substance, another here-and-now individual, which takes no part of the series of here-and-now individuals together constituting a historical individual, like for instance in the case of an insect individual developing through metamorphosis. In the case of substitution in crystals the new Substance is laid down on top of the previous one because of the growth modus of apposition.

Another possible consideration is the view that a crystal is situated rather more closely (than we initally assumed) to the aggregate side of the scale Aggregate ------ Continuum. In this case a crystal would not unequivocally possess (a numerically) ONE Identity, but IS the Identity of its constituents, and then it is not a matter anymore of "me having become someone else", but of many (beings) in which some are replaced by others. But whether a crystal really is such a near-aggregate seems doubtful to me, because of the holistic properties of crystals.

It appears therefore that in inorganic Wholes the chemical composition is a much stronger determinant for the Identity (whatness) of such a Whole, than it is in organisms. In organisms -- as we have seen -- a strong change (or difference) in chemical make-up can be the case, without any accompanying change (or difference) in Identity (whatness) in such an organism.

Or should we distinguish between Identity and Whatness (respectively, Self-being and Essence)? For in one way or another the Identity of the crystal seems to remain constant during the change mentioned (i.e. despite that change). The Self-being (Identity) remains the same, while its Essence (Whatness) changes.

Such considerations possibly also relate to the peculiar problem of being-a-Person.

It is clear that these matters should be further investigated, and the results will, according to me, be interesting.

Remark : The solution could be by realizing, that when (specifically) other atoms enter the crystallization arena and are subsequently deposited, the dynamical law, governing the process, is changed (albeit little), and thus one specifically different (crystal) individual is deposited on top of the previous individual. Both are historic individuals.

A much better solution to the problem of substitution in crystals, however, is as follows :

Remark : The fact that many crystals occur in the form of a twin should be interpreted as the occurrence of a more or less necessary aggregate, i.e. an ordered aggregate, representing a higher-level individual.

In the case of genuine liquids we do not encounter this phenomenon : They are random aggregates of microscopic Wholes, namely molecules, atoms, ions, or mixtures thereof.

Nevertheless there exists something in between them. It is called the Mesophase. It involves liquid crystals (Rheo-crystals). They show an ordering, which is comparable to that of solid crystals (Sterro-crystals), be it weaker.

It is certainly worth the trouble to investigate these Rheo-crystals with respect to their (degree of) individuality, and, with respect to their totality character (which of course closely relates to individuality).

For the time being we again clearly see how subtle and flexible the (concept of the) material individual really is.

Process structures

Besides the mesophase, observed in certain materials, all liquids (and also gasses) can, under certain conditions, generate definite patterns. These patterns are however not static, but dynamic.

So we could for example let water run out of a tap. If we open the tap just a little bit we see a transparent water column. If however we open the tap further this picture changes more or less abruptly. The water jet shows skeins, it looks 'muscular' : a transition has taken place from laminar to turbulent flow.

While in laminar flow the motions of the individual water molecules follow a statistical law of chance, in virtue of which we still can interpret the whole as being an aggregate, in turbulent flow the water molecules are grouped together and forced to act in co-operation as it were, in order still to let through the increased amount of water. Here we have to do with the co-operation of an enormous number of particles. They form a pattern that is stable under the given circumstances. And hence ONE Whole is formed. But this Whole does not consist of permanent components, it is a wholly dynamical totality, like the river of Heraclitus.

It is a process structure.

Such dynamical structures abound in Nature.

After Heraclitus, WHITEHEAD was probably the first philosopher pointing to the process character of Being.

Such a process structure can only exist in an appropriate dynamical regime : A certain degree of transit of material and energy should prevail.

In fact all organisms (in contrast with, say, crystals) are such process structures, be it that they nevertheless possess a fairly concrete character, because their bodies are not genuinely liquid, they find themselves in a semi-liquid state. Also organisms are only stable in a specific dynamical regime of transit of material and energy.

Especially in the simple process structures, like the described turbulent flow, it is clear how a higher-level matter-form composite is generated from water, which itself is (just) an aggregate of molecules : The water now is, as one Whole, the carrier of the turbulence pattern, but this Form is totally dynamic. It is, as it were, constantly created anew, upon new material that is constantly being supplied.

Such structures also show how significant the role of the environment is of such a structure. This underlies the 'inbedding' of Forms within a dynamic environmental context, often causing them -- especially in the case of inorganic process structures -- to be less staked out from that context. In these cases the process structures are less clearly "things". Nevertheless they are genuine macroscopical Wholes in which the parts -- while flowing -- organize themselves into (that) one Whole.

Indeed, in virtue of the close metabolic connection of such a process structure with its environment, its delimitation is, especially in the case of liquid and gaseous process structures, expected to be more or less fuzzy, resulting in a weaker expression of its individuality, as can be observed in turbulent weather systems, which merge more or less smoothly with their environment. In this way the "divisum ab alio" is only (relatively) weakly expressed [ "divisum ab alio" means : separated from others. It is part of the classical definition of "an individual". The other part is : indivisum in se, which means : in itself undivided ].

It is further clear that a here-and-now view of individuality is less appropriate for such dynamic Totalities, because a process is not compatible with a point in time.

And now it is also evident that the concept of "Substance" should be interpreted much more flexibly than is being done in even the most modern form of (Neo)Thomism. The gradual nature of Substance as well as the frequent occurrence of dynamical Substances (process structures) is compelling in this respect.

The process stuctures are known under the name "Dissipative Structures". Their internal order is not possible until they find themselves in a state far from thermodynamic equilibrium, and such is the case if they continually import matter and free (i.e. transformable into work) energy from the environment, and at the same time export matter and entropy ( = a quantity relating to forms of energy which cannot be transformed into work anymore ) into the environment.

When they find themselves in thermodynamic equilibrium their internal structure and coherence usually disappear (See the Essay on Non-living Dissipative Systems ).

In contrast with dissipative systems, crystals are systems, finding themselves in thermodynamic equilibrium. They are static structures residing in energy minima. Despite of this they possess an internal coherent structure, i.e. they have internal order. This is possible at lower temperatures at which the thermal motions of the parts (atoms) are relatively weak, resulting in attraction forces -- if present in a sufficiently strong degree -- becoming predominant. In this way relative stable stuctures are generated (crystals), which, each for themselves form a unity, and which are separated from all other things. In contrast with many process stuctures, crystals cannot evolve (into, say, higher forms, like organisms can), while many process structures are able to evolve to an open end and (thereby) letting new forms appear.

Although the process structures are the most important structures in Nature, crystals are more accessible for a consideration with respect to individuality and a Substance-Accident interpretation.

Organisms are, to be sure, process structures, but they are nevertheless, in their own specific ways, well accessible for the metaphysical considerations mentioned, in virtue of their relative concreteness : They are neither liquid nor gaseous, but find themselves in a semi-liquid state.

A typical property of process structures is the fact that they possess a certain degree of autonomy with respect to their environment, thus having a form of self-being. A disturbance, occurring to them, is often made undone again, and this also happens in growing crystals, because the latter then also have a process nature.

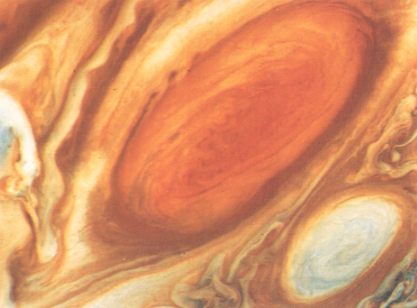

One of the most spectacular process structures is the Great Red Spot on the planet Jupiter (Figure 3). This is a storm system in the higher atmosphere of this planet. It is a kind of whirlpool several times bigger then the Earth, and already existing for at least a few centuries. It is a stable organization of matter and energy through which flows matter as well as energy.

Figure 3. The Great Red Spot on the southern hemisphere of Jupiter. It spins around itself every six days or so, anticlockwise.

(After CAYEUX & BRUNIER, 1982, Les Planetes)

Enantiomorphism

Several species of molecules, but also crystals, can occur in two varieties : A 'left-handed' and a 'right-handed' form. These are symmetrical with respect to each other. They cannot be transposed into each other by any mechanical operation (for example a rotation) whatsoever.

Such left-handed and right-handed individuals are identical to each other, except for their handedness. So such individuals not only are numerically different, but also differ with respect to their handedness. Do they belong to one species of Substance or two?

In organisms this phenomena is also found, but in that case at the molecular level ( NOTE 7 ).

This phenomenon could perhaps be related to what has been said by St Thomas with respect to male and female in animals, insofar as the latter are Accidents consequent on matter according to the ordering of it [of that matter] to a more special Form : De Ente et Essentia, Chapter 6, line 73--80.

----