Substance and Accident

back to homepage

CONTENTS

The general method of Natural Science, is i n d u c t i o n, which means that it observes a series of similar behaviors or similar features with respect to real things and events, and then generalizes them, resulting in a constant pattern to be recognized. After having thus induced (from experience) such patterns, it then sees whether these patterns fit into some more or less preconceived theoretical framework, i.e. it sees whether the observed patterns and similar not yet observed patterns could be deduced from that framework. If this is possible, and if indeed renewed observation verifies events and features predicted by that theoretical framework, then that framwork can be accepted as a good theory explaining those features and events. In doing induction it (thus) presupposes that every uniform thing has a constant appearance (to other things, or to observers) and a constant (type of) behavior, according to its intrinsic n a t u r e or s p e c i e s. That means it always shows the same pattern (or sequence of patterns) and the same behavior, when that thing is, or the conditions are, repeated. If it does not, then the causes for doing so are e x t r i n s i c to its nature. This implies (in fact it is equivalent) that this nature can in principle be repeated over individual cases, i.e. that particular nature or species can exist in (and exist as) a number of individuals. Because of this presupposition about the fundamental and universal structure of uniform things it is possible for Natural Science to generalize from one, or a small number of, individual experiments, for example : In one or more experiments with some individual pieces of Iron one can legitimately apply the findings from those experiments to all pieces of Iron wherever they are, were, or will be.

So according to this presupposition every uniform thing consists of two basic principles (they are principles, not (material) parts!). These are (1) a principle connected with the intrinsic nature (or Identity or Species) of the thing, and (2) a principle connected with the individuation of that nature, and so with the possibility of multiplication of that nature.

In Philosophy these principles are equated with the (metaphysical) principles of Form and Matter respectively. Matter is the ultimate formless substrate of the Form, and this matter-form structure allows change, especially radical change : when this happens the Matter will be informed with another Form or Forms, whereby it is still possible to speak of a (radical) change of something, instead of the total destruction of a thing into nothing and the creation of a new thing from nothing. This form-matter structure of things can also be called their Species-Individuum Structure.

back to contents

In the philosophy of Aristotle and St Thomas Aquinas a distinction is made between First Substance and Second Substance.

We shall elaborate on this within our own vision and findings.

First Substance is the individual uniform thing. It is described in the Essay on Being and Essence. Such an individual cannot be predicated of something else, because it does not inhere in something else (like a property does so inhere).

The 10 Categories, which will be treated of shortly, all refer to the First Substance.

Second Substance is the Essence or Identity (see also the essay mentioned) of that first substance. This Second Substance inheres in the First Substance, and can therefore be predicated of the first. If we assume for a moment that the Essence of any human being is the same and can be denoted with the term ' human ', then we can say

" Socrates (= first substance) is a human (= second substance)."

The Second Substance can be multiplied ('copied') over many individual cases and so gives rise to many individuals (individual human beings). See the Essay on The Principle of Individuation.

Second Substance is the first category of the System of Categories (treated shortly hereafter).

back to contents

First Substance is something 'standing on itself'. It is physically generated from an initial condition : the elements of the dynamical system, plus the dynamical law (going to be the E s s e n c e of the first substance in question) inherent in those system elements. This first substance, as it stands, is a (unique) collection of properties. Each property is, as a property, not ' standing on itself ', because it always is a property of some first substance. They are in a way beings but they are not (self)subsistent. These 'beings' are called a c c i d e n t s. But they need not always to be accidental. Some accidents are directly caused by the essence of the thing, others are caused by extrinsic (extrinsic in relation to the Essence) factors.

We can discriminate between two domains of existence of, and within, the thing (the first substance):

(1) The genotypical domain, this is the domain of the dynamical law and thus the domain of the Essence, and (2) the phenotypical domain, this is the domain of the properties generated by the Essence or generated by external causes (I have borrowed these terms from Genetics, and in the case of Organisms they are especially relevant).

The first substance itself is situated in the fenotypical domain and is the totality of its properties which are also situated in that same domain. If we speak in the context of predication, then we can say that the First Substance is never in a subject, and as a predicate can never be predicated of a subject, while the Second Substance is always in a subject (this subject is the first substance), and as a predicate can be predicated of a subject. Accidents also are always in a subject, but, in contradistinction to Second Substance, accidents belong to the fenotypical domain.

back to contents

The (type of) metaphysics, here developed, is a contemplation from the point of view of the in the real world existing individual uniform thing (first substance). Such a first substance shows, i.e. implies, several ways of being which can be denoted by Second Substance (a first way of being), and the Accidents (several other ways of being). When we ask questions concerning the whatabout of these ways of being, it is possible to give more and more generalized answers, for example when we ask "what is (being) red?" (what does it mean that this individual thing -- pointing to it with my finger -- is red?), we can answer " a color ", and when we ask "but what is a color?", then we can give some more general answer. This proces can go on, but not indefinitely. We will arrive at a highest concept, in this case the concept of Quality. The same applies to other items : When we ask " what is (being)1.50 meter long?", we will end up with the concept of Quantity. And when we ask " what is (being)Socrates?", we ascend from man to mammal to vertebrate to animal to organism to .... Second Substance. All these questions concern a particular first substance, and the answers are given in terms of second substance and accidents in their most generalized form. In this way we arrive at the most general concepts concerning the being of a thing. Those concepts form a logically irreducible diversity. But because the items which are signified by those concepts are all united in an individual (that means, everytime in one and the same individual, for example Socrates), they must somehow form a unity. And because Metaphysics is primarily about existing individual beings (uniform things), and only secondarily about concepts (wich is the domain of Logic), Metaphysics says that those items, signified by those concepts, severally, but also together, form an analogical unity. Analogical because 'being', which is convertible with unity, is predicated of them differently. For example a color, say red, is only in an analogical sense called a being, it always exists in something else which is being in a primary sense (this is the first substance).

It's now time to sum up the basic questions about a first substance -- the Subject -- leading to Aristotle's famous 10 Categories (the examples are his) :

- What the Subject is : SECOND SUBSTANCE , for ex. it is (a)human, (a)horse.

- What the measure of the Subject is : QUANTITY, for ex. it is 2 or 3 yard.

- What the disposition of the Subject is : QUALITY, for ex. it is white, skilled in languages.

- To which the Subject stands in relation with: RELATION, for ex. double, half, larger.

- What the Subject has: HABIT, for ex. having shoes on, being armed.

- When the Subject is: POINT OF TIME, for ex. yesterday, in the year before.

- Where the Subject is: PLACE, for ex. in the Lyceum, on the market.

- What the inner orientation of the Subject is: ORIENTATION, for ex. lying, sitting.

- What the Subject is doing: ACTION, for ex. it cuts, burns (something else).

- What the Subject undergoes: PASSION, for ex. it is being cutted, it is being burned.

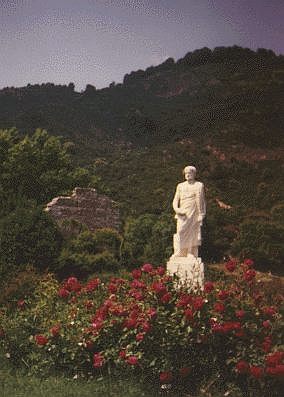

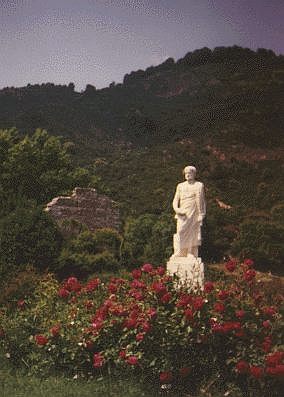

Statue of Aristotle, at Stagira, Greece

Photo by Cynthia Freeland

It is not once and for all established that indeed this is a list of the highest concepts, but it will certainly stimulate the search for them. Especially the categories of Second Substance, Quantity, Quality and Relation are most important. And when they really are the highest concepts, then they cannot be defined, because a definition of a concept requires, among other things, a still higher concept.

Within this scheme there is some more structure to be detected. Thereby it is instructive to realize that the scheme is a scheme of basic predicates, and every predicate signifies something in the real world, about the first substance, the individual thing, which we can denote here as the Subject. Letting this internal structure come out, let's look at a more detailed version of this scheme of basic predicates.

THE PREDICATE SIGNIFIES (in the most general fashion) :

- The Essence of the Subject. This Essence is the SECOND SUBSTANCE.

- Not the Essence of the Subject, but something else. Such predicates are Accidents.

- Something in the subject,

- In an absolute sense,

- Delimitation of Matter.(Matter is one of the two principles of the Essence, the other one is Form). This delimitation is in fact a fenotypical manifestation of Matter, and can be denoted as QUANTITY.

- Fenotypical manifestation of the Form. Form manifests itself as a configuration, and such a configuration can be denoted as QUALITY.

- In a relative sense, co-involving something else. Such a predicate can be denoted as RELATION.

- Points to something else, lying outside the Subject,

- But only partially so,

- Whereby the Subject is the starting term. Such a predicate can be denoted by ACTION.

- Of which action the Subject is the end term. Such a predicate can be denoted by PASSION.

- (Pointing to something else) totally so. But in such a way that that 'something else' contains in it the Subject (The subject is situated in that 'something else'),

- This 'something else' is an extrinsic measure of the subject,

- As far as the Subject is liable to spatial change,

- Intrinsic, according to the ordered dispersion of integral parts of the Subject (and thus its (variable) interior orientation). The corresponding predicate can be denoted as ORIENTATION.

- Extrinsic. That means in relation with surrounding objects (Location). The corresponding predicate can be denoted as PLACE.

The place of a thing is the totality of its immediate surroundings.

- As far as the Subject is liable to change according to time. The corresponding predicate can be denoted as THE POINT IN TIME.

- No measure whatsoever of the Subject, but an outfit of the subject. The corresponding predicate can be denoted as HABIT.

The given characterizations of these fundamental predicates (categories)(remember that they cannot be defined, only cicumscribed) are of course in need of further explication, and moreover cannot count as once and for all settled. We shall elaborate om them further.

Second Substance (and its relation with First Substance) has already been treated in the Essay on Being and Essence.

back to contents

Quantity is first and foremost : extension, i.e. contiguous or continuous quantity (See for a treatment of the contiguum and continuum Reductionism versus Holism). We can also call it dimensive quantity, i.e. quantity having dimensions.

Continuous quantity can be devided and will then give rise to discrete quantity, the product of such a division is a contiguum. The division gives rise to parts and those parts can be numbered and counted. So we might be tempted to state the following :

" Every uniform thing extends itself in space and time, and is spatially divided from other such things, because they occupy different positions in space, itself a continuous quantity ".

But this is not quite correct, because it gives the impression that Space is somehow given, and even : first given. But space is a derived concept. The idea of space is derived from our observation that things are spatial, things are themselves extended. So space is not some sort of pre-existing recipient which gives room for things to be placed in.

So our basic notion of continuous quantity is not space, but extension (of a thing). Extension cannot exist by it self, but always is extension of something (When we abstract from that 'something ' then we have pure extension which is the subject of geometry, or more generally of mathematics). Limiting ourselves to the study of the material world, we always have to do with an ens extensum, i.e. an extended being. The latin word ens means a being, and the latin word extensum means spatial, extended. In fact the concept of spatial is to narrow, because a thing can also be temporally extended (We must not say extended in time), so " extended " renders extensum best. But here we are most concerned with spatial extension.

Can we define the ens extensum ? Let's give it a try :

Something that has parts lying outside each other.

That sounds nice. But extension (extended, extensum) is already presupposed in the notion of " (lying) outside ", so we (try to) define (ens) extensum with (something that is) extended (extensum), and that is obviously not a very informative definition. It is better called a circumscription, stating the meaning of the word (ens) extensum.

We can try other definitions but we will find out that we cannot discover a more basic concept. Extension (of things) is something primarily given.

Quantity penetrates all material things even in their qualitative aspects. For example a color (which we can interpret as being a (certain) quality) is not only a color of a thing with extension (because of which the color also has -- be it in an accidental way -- extension), a color also has intensity. Intensity has a special quantitative aspect, different from pure extension.

Every uniform thing is quantified, but the actual quantitative determinations are different among different things. Such a determination can belong either inseparably to the thing in question, in that case we say that it belongs per se to the thing, or it does not belong inseparably to the thing in question, in that case we say that it belongs to the thing per accidens. Let me give an example. The values of the angles (and thus a quantity) between the faces of a crystal of a certain sort do not change, they are constant (i.e. they form a constant pattern) among the individuals of the sort in question. On the other hand we can see that the magnitude of a crystal (which we could express in terms of its volume, and which is also a quantity) is not constant nor specific among the individuals of the same sort of crystal.

(We can define the sort -- species -- of the crystal by stating its internal symmetry plus its chemical composition , which is a fenotypical effect of the Essence of the crystals in question. This Essence itself is situated in the genotypical domain and is the specific crystallization law that gave rise to the crystals in question) .

Quantity plays an important role in individuation , because an individual is limited to certain dimensions (height and length and width) and separated from other individuals by the division of space (continuous quantity).

back to contents

Quality is, in a way, harder to understand than quantity, and is, like quantity, not strictly definable.

Quality as a factor of observability

When, in Natural Science one uses a mathematical formula, then such a formula always contains variables which point in one way or another to certain sense observations of the material world. So to assess what is being represented by such a variable one has to look to the specific ways in which these variables are observed and measured. This would not be the case when the world would be of a pure quantitative nature only, devoid of any content, quality. In such a world any observation would be impossible.

So quality stands in direct relation with observation, i.e. with the possibility of something being observed by the senses, including the use of sophisticated instruments like microscopes or telescopes and also the devices which let us observe indirectly via certain effects caused by the properties of the observed thing.

Quantitative relations, for example a length, demand, for being observable, a qualitative contrast in order to 'see' the length begin and to see it end. This can be realized already by means of an intensity-difference of a same quality (so for the difference to exist, a quality must be presupposed), or by means of different qualities. So Natural Science presupposes in physical matter a factor, which makes the quantitative relations observable, and we can call this factor the qualitative aspect of physical matter (See Van MELSEN, 1955, Natuurfilosofie (written in Dutch)). But also the other way around Natural Science presupposes in every quality a quantitative aspect. This aspect is the intensity of the quality, and can be measured. So quality and quantity interpenetrate each other through and through : although they are diverse and not reducible to one of them, they are not separate, i.e. they do not and cannot exist separated from each other, in the Real World (See for the distinction between the Real World and the Ideal World, the Essay on The Universal).

Quality as figure

Alongside the forgoing it is also possible to approach the concept of quality from the concept of figure or conFIGURation . A figure is a pattern of whatever entities (or should we say elements). These entities are spatially extended from each other in a certain way. So a figure is an interpenetration of quantity (' spatially extended ') and quality (' in a certain way '). Such a configuration can be of microscopic or submicroscopic dimensions, for example an atomic configuration (i.e. an arrangement of atoms) resulting in molecules. Larger aggregates of such configurations -- for example a large assemblage of molecules of the same sort -- can interact with light in such a way that we see a certain color when the reflected light strikes our eyes. A change in such a configuration will result in a change in either the intensity of the same quality or a change into another quality. Most qualities we directly know of are in fact each by themselves resultants of many microscopic interactions. At the basis lie the configurations.

What then is the precise status of a figure? Is it quantity or quality?

When we consider a figure, say a triangle in Mathematics, we do the following : within the continuous field of points (a point set) we deliberately emphasize certain points, i.e. a certain subset of points, which together form a triangle. In fact all the points of the field are equivalent, they are just points. But from outside we (our contemplating minds) give some points of the field a special status in such a way that we now discriminate between a certain subset of the field and the rest of the points. We discriminate a triangle. Because such a mathematical figure is not only extension, it is (also) quality. But this quality is stipulated -- we could say ' created ' -- by us.

However it is only a quality (with its implied quantity of course). It is not the quality of something, because the elements, of the pattern are only points with no content (they are not themselves patterns). The elements (the points) of the mathematical space did not and cannot by themselves generate the mathematical pattern. It is we who stipulated the pattern. So a mathematical figure has no substrate, it is a quality without substrate, and so is not a thing, not a real being. The mathematical figure is only a geometrical quality. That's why it does not act, and by consequence is not observable (with the senses). A geometrical quality is not a full quality.

Also in material reality (in contrast with mathematical reality) a figure is a quality. It is a pattern, a STRUCTURE. But here it always is a quality of something. It has a substrate. This substrate is equivalent to the elements of the figure. The figure is a configuration of its elements (think of molecules as being a conFIGURation of atoms). Those elements are themselves patterns, they have content, not only location, like the mathematical points of a mathematical figure (pattern). That's why specific action is possible. A figure from the real world, as a figure of something, i.e. a figure and its substrate - and thus a thing -- shows specific active behavior. And so such a full quality makes its possessor observable.

Such an intrinsic configuration, and also all the intrinsic subconfigurations, are generated by a dynamical law, which is the Essence of the thing in question. The dynamical law generates all the qualities and their inherent quantities which together form the individual thing, the first substance.

It is tempting to consider a length (which we interpreted as a quantity), as a quality, because of the delimitation it implies. But a length is not a figure, it even is not a line, but an amount of extension (in one direction). In the same way we can say, a volume is not a, say, cube, it is not a figure, but an amount of extension in several directions, and thus a quantity.

So to reflect once more about the difference between quantity and quality, we can say (1) that quantity is extension (continuous quantity), (2) when this extension is divided, then quality is being introduced, resulting in a figur, a pattern, (3) the multitude, resulted by the division of (pure) extension, considered as multitude, then is discrete quantity.

But how can a figure show intensity? I think that intensity is a derived property. Certain microscopic molecular configurations (and thus figures, patterns) do have some global macroscopic effects when they interact with, say, light, and give rise to colors. The colors themselves are the subjective aspects (they depend on the information prossessing properties of the human brain), the emitted light with the corresponding wavelengths are the objective aspect of this global effect. The intensity of the quality has its seat in this global effect, and can be measured, roughly by our senses, and more accurate with instruments, that will make use of the fact that these intensities in turn can be made to produce quantitative effects, and so we measure with thermometers and all kinds of other calibrated instruments. But the final cause of a change in intensity must be a change in the underlying pattern (figure).

Such patterns -- being qualities -- need not only be spatial patterns. The patterning can also involve a patterning in time. In that case the quality cannot be contemplated, and also not be observed (as existing) at a point in time, but only during an interval, so for example all kinds of vibrational phenomena, like tones (in music) and colors (of light).

SO IN GENERAL QUALITIES OF THE REAL WORLD ARE SPACE-TIME PATTERNS.

So it is clear that any quality presupposes extension, be it in space or in time or in both.

From the theory of dynamical systems we know that many systems can generate patterns from unordered initial conditions. In general these patterns cannot be predicted in advance even with respect to simple dynamical systems. So quality can be generated.

On the other hand it is possible that a chaotic, disordered state will be generated from an ordered initial condition. So quality can be destroyed.

When we consider a quality in the real world (in contradistinction to the immaterial mathematical world) to be a figure, whose elements are again figures, we can wonder if that could go on indefinitely. Probably it will not. At very small scales the concept of distance, and with it the concept of extension, will probably cease to have any meaning whatsoever. That means that also configuration, and by implication quality, will not exist at those scales.

Of the accidental Categories only Quantity and Quality are in the subject in an absolute way. And because our investigation is primarily concerned with intrinsic principles of a uniform thing, we shall conclude our contemplation of the Categories.

The next Essay, consisting of three Parts, will treat the "accidents", which in the present Essay figured as accidental predicates, in a more general and comprehensive way. We will call them collectively "determinations". But we should bear in mind that the latter term is somewhat broader in its signification.

*********************

back to contents

back to homepage

.