e-mail :

"The mathematical number is the dominant principle of the World, that moves and organizes matter and provides it with SHAPE."

Pythagoras

"Die äussere Form jedes organischen Individuums ist immer ebenso gesetzmässig wie diejenige jedes anorganischen Individuums und daher einer mathematischen Erkenntnis (Ausmessung und Berechnung) zugänglich."

E. Haeckel, Generelle Morphologie der Organismen, 1866

"My sole purpose is to correlate with mathematical statement and physical law certain of the simpler outward phenomena of organic growth and structure or form, while all the while regarding the fabric of the organism, ex hypothesi, as a material and mechanical configuration."

D'Arcy Thompson, On Growth and Form, 1942

Ernst Haeckel was born in Potsdam, Germany, in 1834. Most of his life he worked in Jena (Germany) as a Zoologist. He concentrated on lower marine animals, especially Radiolarians (unicellular marine organisms having complicated and often beautiful skeletons consisting of spheres and needles). Besides this specialism his knowledge was very extensive indeed, covering in fact the whole organic world including plants. His scientific and philosophical life became to be dominated by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection, published in 1859. Haeckel was excited by this new theory, because it matched so well with his own ideas about the status of the organic world. It was his conviction that all organisms, including man, were perfectly natural, i.e. they did not distinguish themselves from inorganic entities by their having supernatural powers. The organic world was just as 'mechanical' as the inorganic world. And man is just as biological as any other organism. There is no place for 'immaterial souls'. The inorganic world, the organic world and the world of man were ontologically indistinguishable. Haeckel called his position "monism" (versus dualism). Indeed the theory of evolution, as presented by Darwin closed the gap between lower and higher organisms, and of course could be extended downwards to include the origin of organisms from inorganic entities, and it could also be extended upwards to include the origin of man from higher animals. Such a wholesale theory of evolution would certainly support Haeckel's monistic ideas : The first organisms evolved "mechanically" (nowadays we would say physico-chemically) from inorganic beings. Then these pristine organisms developed, again "mechanically", i.e. by natural selection, into higher and higher organisms, and from one of their species man finally evolved. Because of his natural origin he does not possess supernatural elements.

Let us translate this title page :

General Morphology of Organisms

General Outlines of the Organic Science of Forms, mechanically based on the Theory of Descent as reformed by Charles Darwin,

by Ernst Haeckel

------------------

Volume I :

General Anatomy of Organisms

"AND YET IT'S MOVING!"

[This was an exclamation of Galileo concerning the movement of the Earth, against the opinion of the church.

-------------------

BERLIN.

Printing and Editing by Georg Reimer.

1866.

With this Haeckel is alluding to the conflict between the theory of evolution and the dogmas of the church]

With two promorphological plates

This work is, according to me, a masterpiece. In an extraordinary systematic and clear fashion Haeckel presents two new disciplines, Organic Tectology and Organic Promorphology.

His T e c t o l o g y investigates the six types or stages of organic individuality :

Cells, Organs, Antimers, Metamers, Persons and Colonies.

What Cells and Organs are should be clear (Organs are made up of cells). The others call for some explanation : Antimers (counterpieces) are parts (of an organism) that lie either (exactly) opposite to each other, like the left and right halves of bilateral organisms, or are grouped about some imaginary axis, like the arms of a starfish. Metamers (sequential pieces) are parts that lie behind each other, forming a string, like we see in earthworms. Persons are built up from cells, organs, antimers and metamers. In the animal kingdom a p e r s o n ( P e r s o n a, or P r o s o p o n ) generally is a whole animal, while in many plants it is a part, namely an

off-shoot ( C u l m u s, or B l a s t u s ). Many off-shoots together make up a Colony ( C o r m u s ), for instance a tree.

So the lowest stage of individuality is (represented by) the cell (either as a part of an organism or as a whole organism), then we get the organ (it consists of cells), then we get the antimer (it consists of organs), then the metamer (it consists of antimers), then the person (it consists of antimers and metamers), and finally, as the highest stage of individuality, we have the colony (it consists of persons).

This Tectology thus considers an organism as being built up by a number of morphological units, placed such that they group themselves about or along certain imaginary axes, or on both sides of an imaginary plane. In this way organisms have a different structure than crystals. While crystals are built up by a regular stacking (in three directions) of identical building blocks, all having the same orientation within the crystal and thus displaying a PERIODIC structure (A fact not very well known to Haeckel), organisms possess a TECTOLOGICAL structure.

Well, on this Tectology of organisms a PROMORPHOLOGY can be based.

Haeckel defined his P r o m o r p h o l o g y as the doctrine of the Stereometric Basic Form of Organisms. It tries to assess the symmetries of organismic bodies (cells, organs, antimers, metamers, persons and colonies). However, in his time it was believed that organismic bodies would never yield to a mathematical description, in contrast to inorganic bodies, especially crystals. It was held that organisms were fundamentally different from non-living things, especially that they were not wholly of a physical nature. Indeed, if we want to describe the organic forms mathematically we run into difficulties because their forms are, to be sure, often of a regular nature, but not quite so.

Their forms defy any precise description boasting any generality. Every organismic individual is more or less unique in this respect.

But when we inspect organismic shapes carefully, we can, with some effort, detect some symmetry that lies, as it were, beneath the unwieldy forms. Haeckel's Promorphology tries to uncover these hidden symmetries, by means of geometrically idealizing, i.e. by distinguishing between essential and casual features of the shapes (forms) of organisms. And in succeeding he could show that the forms of organisms were mathematically describable after all. All this was part of Haeckel's effort to close the gap between the non-living and living world.

Having dealt with organic Tectology and Promorphology his "Generelle Morphologie" proceeded to treat of organic development and concluded with some philosophical contemplations, in which, among other things, he considered the concept of the "God-Nature" (Theophysis), expressing his conviction that God is identical to Nature, i.e. God and Nature are mutually convertible.

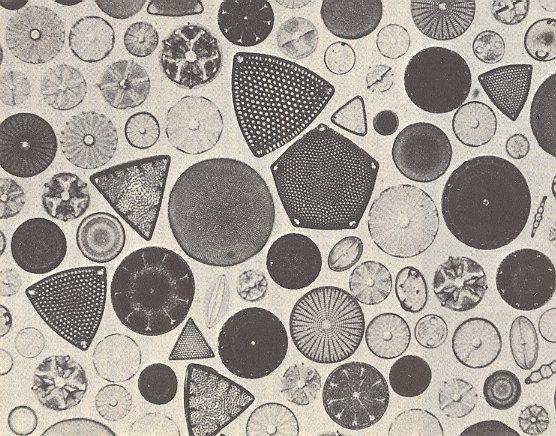

After writing his "Generelle Morphologie" Haeckel continued his special investigations concerning lower marine animals, especially Radiolarians. The latter are -- as was already related above -- unicellular organisms (their dimensions do not exceed a millimetre or two) possessing very complicated shells (skeletons), consisting of hollow perforated spheres and (often strong) needles, in many cases displaying a great deal of geometrical regularity and beauty. When we inspect the many species we see a stunning diversity in their shell shapes. The material of those shells is silica, strontium sulphate or some other substance.

In the meantime Haeckel devoted much of his energy in writing popular books in order to promote Darwin's theory of evolution and Haeckel's own monism. These books became well known. The most famous and influential one was his

Indeed, we can say with firm conviction that Ernst Haeckel was a great biologist, who has contributed an aweful lot to man's quest for the Holy Grail of Biology.

Promorphology or the Doctrine of Basic Form Types of Organisms is the overall Science of the external shape of the organic individuals and of the stereometric basic form that lies beneath that shape. Every scientific account of an organic form should base itself on the corresponding stereometric basic form. That's why this discipline is called PRO-morphology.

As has been already stated, this Promorphology is geared to those natural objects that have a tectological structure, i.e. a stucture that consists of several units that are grouped around one or another imaginary axis, or (are placed) at both sides of an imaginary plane, such that, generally, the orientation of those constituent units differs among each other. In the inorganic world all molecules possess such a structure, while among crystals only some twinned crystals possess it. Many inorganic bodies do not have this structure at all and are (not by coincidence) not genuine beings, i.e. not beings possessing intrinsic unity. All the other natural objects having this structure are organisms, and, indeed they all have that structure without exception. And also their parts are tectologically constituted. That's why we can consider Promorphology as an organic disciplin.

An organism can be shown to be a product of a dynamical system. All the visible intrinsic features of such an organism are thus produced by such a dynamical system, they are expressions of the relevant dynamical law, which I call the ESSENCE of the given organism. Among the many intrinsic features we find the stereometric basic form of that organism-as-a-whole, and also that of the mentioned morphological units that constitute that organism (cells, organs, etc.). Such a morphological unit is for example a flower (which is a person and which itself in turn consists of morphological units). So Promorphology not only investigates the stereometric basic form of the whole plant, but also of its flowers and other parts (morphological units) of it. Generally, it studies the stereometric basic form of all the organic individuality stages mentioned above : cells, organs, antimers, metamers, persons and colonies. These stages we will jointly call "organic individuals"

Let us, before going further, elucidate the type of SYMMETRY that is dominant in Promorphology : mirror symmetry.

An object is mirror symmetric (i.e. possesses a mirror plane) if the object is mapped onto itself when it is reflected with respect to that mirror plane. In other words, the object will remain the same when subjected to the operation "reflection of it with respect to a plane that can be imagined to run through it". In Figure 5. this is explained by means of a 2-dimensional object :

In a given organic individual Promorphology starts to look for preferred (imaginary) axes, i.e. axes that forces themselves upon us as soon as we inspect the object carefully. Next it sees how the symmetry of that given individual can be represented by the poles of such axes. If symmetry is present across such an axis then we call this axis homopolar (equipolar), when it is absent we describe it by saying that the axis is heteropolar (non-equipolar). On the basis of this information we then construct the most simple geometric figure that displays these symmetries. Let me give an example.

The next Figure depicts a Rhombic Pyramid :

This Rhombic Pyramid possesses two mirror planes as the two next Figures show :

Because our organic individual under investigation, namely a human body, possesses only one mirror plane we have to eliminate one such plane from the Rhombic Pyramid. We can accomplish this by erasing one half of the pyramid. If we do so we indeed get a geometric body that admits of three axes to be distinguished while having only one mirror plane, as the next Figure shows. The left image is the resulting rhombic hemipyramid, while the right image indicates some features of the external shape of the human body :

Figure 9. Rhombic Hemipyramid indicating the stereometric basic form of the human body.

Here we have choosen the position of the axial system to be at c, which implies that two axes are contained in the base of the hemipyramid. But of course we can also choose this position to be at the mid-point of cd.

In the stereometric basic form, which we can also call the "promorph", of the human body, as represented by the Rhombic Hemipyramid, we see that the b b axis, connecting left and right, is homopolar, because of the mirror plane (indicated in blue). The axis a c, connecting belly and back, is heteropolar, as well as the axis

A second example could be a common starfish.

The body of such a starfish consists of five similar parts grouped, in a regular way, about an imaginary axis. This axis we can call the main axis, it runs from the mouth of the animal to its back, and is clearly heteropolar. Through the middle of each 'arm' we can imagine an axis, resulting in five equivalent but heteropolar axes. With this we have sufficient information to establish the promorph (= stereometric basic form) of such a starfish : it is a regular pentagonal pyramid. The next Figure shows the base of such a pyramid.

With the help of the coloration in the above Figure we get some idea where to find the five antimers making up the body of the starfish and that of its promorph.

Of course we can set the origin of the axial system in the geometric center of the pyramid. See Figure 11. where we have indicated this alternative location (together with the previous location, for comparison) :

Later, when the whole system of stereometric basic forms is being set up, we will call the above established promorph of the starfish a member of the Promorphological category of the Pentactinota, meaning "five-fold radial bodies".

I hope that these two examples give the reader some idea of what we're talking about. In assessing the promorphs of all sorts of organisms, we'll find (them as) spheres, cylinders, ellipsoids, cones, double-cones, cubes, pyramids, double-pyramids, hemi-pyramids and so on. Especially in lower organisms, like Radiolarians, Diatomeans or Coelenterates, but also in higher plants (flowers), we will encounter a great diversity in their stereometric basic forms.

Promorphology as a system of geometric form development

The system of stereometric basic forms will display an ongoing (ideal) process of symmetry breaking, reflecting a gradual increase of differentiation of organic bodies. We see more and more axes become heteropolar until we arrive at bodies having no symmetry at all but still allow for axes to be imagined. Sometimes it is convenient to indicate such a heteropolarity by the absence of one half of the relevant axis.

Seldom the stereometric basic form is shown directly by an organism, i.e. directly by its observable external shape (A number of Radiolarians do so). So generally the promorph is an ideal abstraction, but nevertheless always based on the organism's structure. The next Figure depicts a few such promorphs in order to introduce the reader further before embarking on the systematic treatment of Promorphology.

Now that we know something about the way the axes and their poles determine a promorph we can begin to derive the main promorphological categories.

In the f i r s t g r o u p this center is a c e n t e r o f s y m m e t r y, which means a definite point such that reflection in this point maps the body, possessing a center of symmetry, onto itself. The next Figure illustrates a form -- here consisting of two (isolated) planes (faces) only -- possessing a center of symmetry.

Figure 15. Center of Symmetry.

The item, as depicted here, and possessing a center of symmetry (and only a center of symmetry) consists of two asymmetric faces related to each other by a center of symmetry, which means that every point of such a face is reflected in a same point, the center of symmetry ((all this)indicated by the red lines and their point of intersection. Every part of the item can also be found at the opposite side of that point at the same distance. As we will see, this symmetry element only plays a minor role in Promorphology.

But the forms possessing such a center of symmetry only then belong to that first group when their center of symmetry is their only symmetry element. Although we can draw axes through this center, those axes are, apart from the fact that they definitely go through that point, not definite, firstly because there are no axes that stand out among the other axes, i.e. they all are equivalent, secondly because their length is not definite : all lengths can in principle occur in such an object. This in contradistinction to a Sphere, the mid-point of which is, it is true, a center of symmetry, but the latter is not the only symmetry element of the sphere. The infinitely many axes that can pass through the sphere's center are all equivalent, and in this sense there are no definite axes, but they all have the same length, and in this sense they are definite. Our group of forms, on the other hand, possessing just a center of symmetry and nothing else, do not possess definite axes, and we will classify them as Anaxonia, meaning bodies in which definite axes are absent. And of course the totally irregular forms which do not have even a center of symmetry -- they have no center whatsoever -- also belong to the Anaxonia.

The s e c o n d g r o u p of bodies (forms) possessing a center, consists of bodies in which a center can be indicated such that through it d e f i n i t e a x e s can be drawn. They will promorphologically be classified as Axonia, meaning forms possessing one or more (imaginary but definite) axes. It is this group with which we're going to deal extensively, because it contains many subgroups, constituting the bulk of the promorphological categories. Of course the Anaxonia (the Anaxonia acentra as well as the Anaxonia centrostigma) will be dealt with either, but that's not going to be a long story.

In assessing the stereometric basic form (promorph) of a given organismic individual we strictly adhere to the Monistic Basic Law of Promorphology :

The ideal stereometric basic form of such an individual is determined by the constituting (ideal) parts (constituents) of its body : So only after a tectological study (See for that the above documents of this website) a promorphological assessment can follow. However the promorphs as such can of course be derived geometrically, and this we will do in due course. As has been said, the Anaxonia acentra are such that no ideal stereometric basic form can be determined, while the Anaxonia centrostigma only consists of bodies having just a center of symmetry. The latter bodies are seldom encountered in the organic world (in contradistinction to the world of crystals where we find them as crystallized in the Pinacoidal Class of the Triclinic Crystal System. So our main concern will be the Axonia, i.e. forms allowing for definite axes to be drawn.

The geometric derivation of the promorphological categories thus consists in classifying all the diverse forms of the Axonia on the basis of their ideal geometric kinship. They derive from each other by the progressing differentiation of their constituent parts. Sometimes a form can be derived from several other forms, in which case the prevailing organic genetic relations between the relevant organisms will be decisive. So Promorphology, even in its geometric derivations, keeps being in touch with Biology.

The Axonia can be divided according to the nature of the CENTER :

All axes can radiate from one point. So the center of the bodies representing this group is a point. Through this point mirror planes can either be imagined in all directions :

Homaxonia ( Bald Spheres, H o l o s p h a e r a ),

or, at least three such planes that are perpendicular to each other can be imagined to go through that point :

Polyaxonia. In the latter case the resulting geometric body is not a sphere, but can be fit neatly within a sphere (endospheric polyhedra), they are faceted spheres ( P h a t n o s p h a e r a ).

All these forms (Spheres and Endospheric Polyhedra) we will call (Axonia) centrostigma (not to be confused with the Anaxonia centrostigma).

In the representatives of a second group (of the Axonia) the center is represented by a line (instead of a point). If an infinite number of mirror planes intersect in this axis we obtain forms like cylinders, cones, and the like. We will call such forms Monaxonia.

If, on the other hand, the number of mirror planes that intersect that axis is finite, then we call the group consisting of such forms Stauraxonia. To this group belong single pyramids, regular or flattened, and bipyramids, regular or flattened. A part of these Stauraxonia, however, consists of hemipyramids. And because the body center of representatives of the latter is a plane, they do not belong to the present group. The rest of the Stauraxonia possess at least two mirror planes containing the main axis, implying that the center is a line, and they do belong to the present group.

All Monaxonia, and Stauraxonia with at least two mirror planes, together make up our group called Centraxonia.

Representatives of the third group (of Axonia) have their center represented just by a plane ( P l a n u m c e n t r a l e ). This plane is the only possible mirror plane of such a form. In this group we will see hemipyramids, they are halves of single (regular or flattened) pyramids. Except one axis, the left-right axis, all axes are heteropolar.

A part of such forms, called Amphipleura, either can have more than four antimers -- like we see in the irregular sea urchins -- implying that they allow for at least five radii to be present, or they have three antimers, allowing for three radii to be present -- like we see in, say, (the flowers of) Orchids.

A second part is formed by the Zygopleura in which there either are two antimers or four antimers, allowing for two and four radii to be present respectively.

So the group of forms in which the body center is a plane consists of two divisions, the Amphipleura and the Zygopleura. The exact difference between the two and the reason to assess them as different divisions will be explained in the course of the ensuing systematic Promorphology.

The whole group (Amphipleura + Zygopleura) will be called Centrepipeda or Centroplana.

The geometric form development does not start with an Anaxonic form but with the Homaxonic form (sphere).

But when the differentiations of Allopolygona become progressively more regular, we'll get first of all the Isopolygona, these are endospherical polyhedra with non-congruent but nevertheless similar faces. When the differentiations have finally become completely regular we'll get Polyaxonia rhythmica, these are fully regular polyhedra, the faces of which are congruent.

Further differentiation leads to the Protaxonia. These are forms in which one axis is especially conspicuous, and can be called the main axis. The group of Protaxonia comprises cylinders, ellipsoids, eggs, lenses, cones, bicones, columns, pyramids, bipyramids, hemipyramids and quarterpyramids.

There is one particular type of organic shape that is widespread among organisms, namely the Spiral, which doesn't seem to fit in any promorphological category. Haeckel considered the spiralled organisms as a result of unequal growth of their right and left body halves. He therefore assigned them to the "Dysdipleura". The Dysdipleura are organic forms originated from purely bilateral conditions, conditions like we encounter in most Arthropods (insects and the like) and Vertebrates (Fishes, Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals). All these animals have as a characteristic feature of their basic form a single mirror plane separating the left and right body halves in such a way that those halves are symmetrically equal with respect to each other. Such animals are promorphologically assigned to the Eudipleura. In some of them, however, for example in the Pleuronectids (Flatfishes), one body half is developed markedly differently with respect to the other, and they (i.e. those flatfishes) are then assigned to the Dysdipleura. All their axes are heteropolar, including their lateral axis. In some cases the unequal development of the right and left body halves can be imagined to cause the body to assume the form of a spiral, and such a form Haeckel also assigned to the Dysdipleura.

With respect to spirals, however, we cannot agree with him :

Whether or not the spiral form of an organism is brought about by the unequal development of both body halves, the resultant form, the spiral, is a wholly new form, deserving to be a promorphological category of its own. Moreover the spiral is very common, and certainly not some small deviation from one or another well-established form. Further it shows a bewildering diversity among organisms (Snails, Ammonites, etc.). We accordingly must establish a special promorphological category receiving all the spiral forms, a category not recognized as such by Haeckel.

How do we assess the spiral form promorphologically?

Well, the spiral form of an organism, (or) of a part of an organism (for example its horns), or of its shell, clearly indicates that the main axis of the body (part) is spirally curved. On the basis of this property we will call the promorphological category representing all spirals (provided that they are permanent structures) "Spiraxonia". As such they will be the Third Suborder of the Protaxonia (The First Suborder represents the Monaxonia, while the Second Suborder represents the Stauraxonia). The Spiraxonia will be dealt with after the (long) study of the Stauraxonia. There we will define two main types of spirals of which the most important one is the equiangular spiral (also called logarithmic spiral) which we find in all shell bearing snails, and also in other animals.

When we want to describe the s h a p e of an organic individual (that can also be a subordinated form individual, for example a metamer), we first of all must assess the morphological c e n t e r of that individual. If it does not have a natural morphological center then we more or less arbitrarily indicate an appropriate and convenient point and interpret it as the individual's center.

In order to get some idea as to how to accomplish the morphological abstraction in as objective as possible a fashion, I will give a few examples.

The exit of the stone canal in regular sea-urchins, the madreporite, should (morpho)logically and functionally lie in the center of the antiperistome, i.e. right on top of the sea-urchin's skeleton. But at that location the gut (which is an axial organ) already ends up with the anus. So the madreporite comes to lie a bit excentric. So the radial regularity of such a sea-urchin would be destroyed by it, when we take this position of the madreporite into account. It is clear that we should not take that excentric position into account and assess the basic form of the (regular) sea-urchin accordingly.

The heart of every human being is situated on the left body half, and as such destroys (with some other excentric but constant features) the bilateral symmetry of the human body. It is probable, however, that this excentric position is demanded just by the available space in the body and nothing else. The heart must -- it seems -- lie excentrically. But of course it could have been positioned in the right (in contrast to the left) body half. That it is actually situated on the left side is just a historical accident (in the evolutionary development of man and his precursors). So we can, in a promorphological consideration, leave out this excentric position all together. The same will apply to some other organs of the human body. Thus also here we can leave those positions out (And of course all the accidental morphological features were already left out anyway). The result is that the promorph or stereometric basic form of the human body is bilateral symmetric in the strict sense, i.e. its promorph is that of the Dipleura.

So in all this we see that Promorphology is about i d e a l forms (shapes) of organisms, forms, that are mathematically describable in a simple way, and that lie at the foundation of the a c t u a l shape of the given organic individual.

When the given organic individual does, on the other hand, admit of a natural center, then we must assess whether this center is a point, a line, or a plane.

Having thus established the center of the given organic individual, we now draw lines radiating from the center, and describe what we see when we go along each radius. We measure all the distances involved and will finally end up with a detailed description of the shape of the given organic individual.

But this procedure, although it thus successively describes the shapes of all existing organic individuals (in so far as they represent biological species), is of limited value as soon as we put emphasis, not on the different organic individuals (representing species), but on f o r m (shape) itself. Only when we concentrate on form (shape) itself and see how the different forms are materialized in, and distributed over, the existing organic individuals, then we approach a p r o m o r p h o l o g i c a l consideration of organic individuals, i.e. then we see certain forms (shapes) in them which are often not actually possessed by them, but from which their actual forms (shapes) can be d e r i v e d. So we apply some sort of a b s t r a c t i o n with regard to form (shape).

Well, when this abstraction is such that it concentrates on s y m m e t r y , and is moreover such that the resulting form is describable in simple mathematical terms, involving summetry axes and planes, then we are doing Promorphology.

Concentrating (mainly) on symmetry, this abstraction procedure can be described as follows :

Only relevant morphological features that are c o n s t a n t within the biological species (but often relating to a cerain individual developmental stage) are being considered. They are PER SE determinations of the given organic individual.

So we first of all abstract from ACCIDENTAL morphological features, i.e. we do not take them into account when assessing the promorphological status of the given organic individual.

However, if we pursue the matter this way, i.e. if we take into account ALL per se morphological features of the given organic individual (under investigation), then we will, after having investigated all organisms in this way, end up with only a very few b a s i c f o r m s. These will be (among others) the Anaxonia, Spiraxonia and Dysdipleura. The resulting system of organic basic forms will obviously be poor, and not very instructive with respect to obtaining a general insight in organic form (shape). So the abstraction procedure has not gone far enough. We must, in order to get this insight, abstract (i.e. not consider) many more morphological features, and that means here, we should not consider many per se morphological features, in order to obtain the true b a s i c form (which as such has become in many cases, highly ideal). Of course the main difficulty in such an approach is how to s e l e c t those per se morphological features, that should be omitted from the promorphological description, and which ones should be retained, without making the results subjective.

This is not easy to accomplish, and because of that our promorphological assessment (of the promorph of given organic individuals) are liable to contain errors, that later turn up as such. Sometimes new promorphological categories must be erected to accomodate (the promorph of) certain (peculiar) organic individuals or species. So our system will be under constant revision, and I hope I will receive suggestions from anybody who is interested in the matter.

With all this our Introduction to Promorphology has come to a conclusion. The next Essays (documents) are concerned with a SYSTEMATIC PROMORPHOLOGY, that is complete, i.e. all the possible stereometric basic forms will be derived in a systematic way, as indicated above.

REMARK : The improvement of Haeckel's promorphological system will, in addition to restoring errors -- consist of the introduction of new promorphological categories, for example, the Anaxonia centrostigma, the Homopola sigmostaura (sigmoid forms with a mirror plane), Heteropola gyrostaura (sigmoid forms without a mirror plane), and Spiraxonia (spiral forms).

This (whole) website focusses on the ONTOLOGY of natural material objects. These objects are supposed to be generated by certain dynamical systems (as is explained in the First Part of Website). This means that also all their properties are generated by those systems. The dynamical law of such a system is then considered to be the E s s e n c e of the generated object, and as such resides in the latter's ontological core. The properties of the object are the visible products of that dynamical system and thus are derived from the Essence, in the sense that they become manifest, and as such reside in the object's ontological periphery (but still being intrinsic properties) (In fact we should say that the Essence of the object becomes manifest by way of the object's intrinsic properties). One of these properties is STRUCTURE. And two important aspects of structure are SYMMETRY and PROMORPH (= stereometric basic form). The latter accounts not only for symmetry, but also for the number and arrangement of antimers. The former is treated algebraically as s y m m e t r y g r o u p s in the documents on Group Theory.

Now we could ask ourselves "what is the precise o n t o l o g i c a l s t a t u s of symmetry groups and of promorphs, i.e. do they exist as such independently of our thinking, and if so, in what way do they so exist?" And this, of course, leads us to the general question of the ontological status of whatever mathematical structure (geometric or algebraic).

Well, this question is anwered in a document within the Group Theory Series. In it we also elaborate more on what a promorph in fact is or should be, and in what it differs from the corresponding symmetry group. To see this document in a separate window (and then -- if you happen to land at the very beginning of that document -- scrolling down a bit till you read for the second time "Ontology of symmetry groups . . . "), click HERE. After having consulted the document, close it, and you will be back where you were. If you want to see this document in its context, click on SEQUEL TO GROUP THEORY in the left frame, and then go to SUBPATTERNS AND SUBGROUPS Part XIII, and scroll the document down a little, as indicated above.

e-mail :

To continue click HERE to actually begin with Systematic Promorphology.

back to retrospect and continuation page

back to Internal Structure of 3-D Crystals

back to The Shapes of 3-D Crystals

back to The Thermodynamics of Crystals

----