The Hexagonal Crystal System is based on four crystallographic axes (although of course any face could be described already by three axes, using four axes is more convenient).

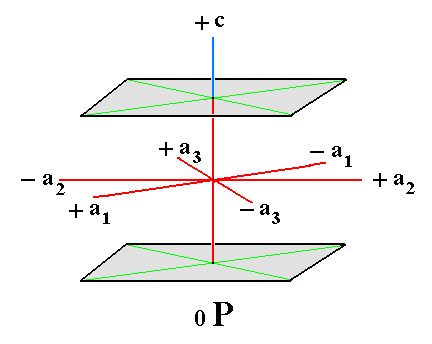

The system of crystallographic axes of the Hexagonal Crystal System consists of three equivalent (i.e. interchangeable) horizontal (equatorial) axes of which the positive ends make an angle of 1200. They are denoted by a1, a2 and a3. They all lie in the same (horizontal) plane. When we erect a line perpendicular to this plane and passing through the intersection point of the three horizontal axes, we have the fourth crystallographic axis, the c axis. The upper end of the c axis is provided with a + sign, the lower end with a - sign. Also the other axes are provided with such signs as indicated in the next figure, that depicts the configuration and orientation of the three horizontal crystallographic axes.

Figure 1. The three equatorial (horizontal) equivalent crystallographic axes (red lines) of the Hexagonal Crystal System. These axes are sometimes denoted as a, b and d axes.

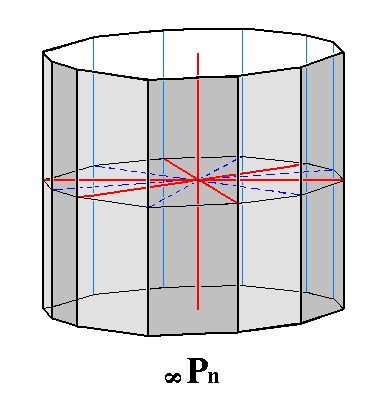

The next Figure gives an oblique view of the system of crystallographic axes with the c axis vertical.

Figure 2. The Hexagonal axial system, seen with the c axis vertical.

Indexing of faces

The method of indexing of faces of crystals belonging to the Hexagonal System is not exactly the same as in the case of crystals of the other systems. For the Hexagonal System the method of Bravais-Miller is adopted. In this method the indexing of a face involves four indexes, h, k, i and l.

Because in the Hexagonal System four axis are used the Weiss symbol also contains four symbols, referring to the a1, a2, a3 and c axis respectively. In determining the Bravais-Miller indices we take the reciprocals of the Weissian derivation coefficients and convert them to whole numbers, and place the resulting set of indices, characterizing a certain crystal face, between round brackets ( ). When we want to indicate a Form (generally consisting of a set of faces) by one of its faces we put the set of Bravais-Miller indices between braces { }.

The next figures show how to index faces of the Hexagonal Crystal System (In fact we show it with respect to the three horizontal crystallographic axes).

|

Figure 3. The indexing of the face A , characterized by the Weiss symbol a : ~a : -a : c ( The sign " ~ " stands for infinity) (and the reciprocal of infinity is 0). It is a face of a pyramid. The derivation coefficients are respectively 1 infinity 1(-) 1. The reciprocals of the derivation coefficients are respectively 1/1 1/~ 1/1 (-) 1/1, and these are equal to 1 0 1(-) 1 respectively. So the Bravais-Miller symbol for this face is ( 101*1 ) (For the sign * see the remark below). |

Remark : In the Figure we see that the a3 axis is cut at its negative end. To indicate this, one places a minus sign (-) above the relevant index. Because of typographical reasons we, here on this website, place an asterisk (*) after the relevant index instead.

|

Figure 4. The indexing of the face B , characterized by the Weiss symbol a : a : -1/2a : c . It is a face of another pyramid. The derivation coefficients are respectively 1 1 1/2(-) 1. The reciprocals of the derivation coefficients are respectively 1/1 1/1 2/1 (-) 1/1, and these are equal to 1 1 2(-) 1 respectively. So the Bravais-Miller symbol for this face is ( 112*1 ). (For the sign * see the remark above). |

Hermann-Maugin notation of symmetry content of hexagonal Classes.

In the Hermann-Maugin notation the first number refers to the principal axis of symmetry coincident with c. The second and third symbols, if present, refer respectively to symmetry elements parallel with and perpendicular to the crystallographic axes a1, a2 and a3. Equivalently expressed, the second symbol refers to symmetry elements each of them parallel with a horizontal crystallographic axis, while the third symbol refers to the bisectors between these axes.

| Division | Class | mirror planes |

axes | cs |

| Holohedric | Dihexagonal-bipyramidal 6/m 2/m 2/m |

1 + (3 + 3) | one [6] three + three [2] |

+ |

| Hemimorphy of Holohedric |

Dihexagonal-pyramidal 6 m m |

3 + 3 | one [6] p. | - |

| Pyramidal Hemihedric |

Hexagonal-bipyramidal 6/m |

1 | one [6] | + |

| Hemimorphy of Pyramidal Hemihedric |

Hexagonal-pyramidal 6 |

- | one [6] p. | - |

| Trapezohedric Hemihedric |

Hexagonal-trapezohedric 6 2 2 |

- | one [6] three + three [2] |

- |

| Rhombohedric Hemihedric |

Ditrigonal-scalenohedric 3* 2/m |

3 | one [3] three [2] |

+ |

| Rhombohedric Tetartohedric |

Trigonal-rhombohedric 3* |

- | one [3] | + |

| Trigonal Hemihedric |

Ditrigonal-bipyramidal 6* m 2 |

1 + 3 | one [3] three [2] p. |

- |

| Hemimorphy of Trigonal Hemihedric |

Ditrigonal-pyramidal 3 m |

3 | one [3] p. | - |

| Trigonal Tetartohedric |

Trigonal-bipyramidal 6* |

1 | one [3] | - |

| Hemimorphy of Trigonal Tetartohedric (Ogdohedric) |

Trigonal-pyramidal 3 |

- | one [3] p. | - |

| Trapezohedric Tetartohedric |

Trigonal-trapezohedric 3 2 |

- | one [3] three [2] p. |

- |

Figure 5. Stereogram of the symmetry elements of the Dihexagonal-bipyramidal Class, and all the faces (face poles) of the general Form.

The basic Form of the Hexagonal System is the (primary) protopyramid.

It is itself based on some existing crystal species. So by definition all the intercepts (i.e. pieces cut-off from the crystallographic axes by the faces of the pyramid) are of unit length.

Its basic face, the upper front face, has as its Weiss symbol a : ~a : -a : c (where " ~ " means infinity).

From this face we can in turn derive the hexagonal protopyramid by applying the symmetry operations of the present Class to it, yielding a Form that possesses all the symmetries of the Class. Like in the Tetragonal System we will use the stereographic projection of the symmetry elements and face poles to derive all the hexagonal holohedric Forms, of which the most basic one is the mentioned hexagonal protopyramid (= type I pyramid).

The position of the face a : ~a : -a : c in the stereographic projection of the symmetry elements of the Class is shown in (1) of Figure 6.

When we apply the symmetry elements of our Class to this face, then the following happens : The 6-fold rotation axis generates five new faces, so we now have six faces. Their configuration complies with 6-fold rotational symmetry. It is a six-sided monopyramid. Next we reflect this result with respect to the equatorial mirror plane resulting in a bipyramid. The other symmetry elements do not have any further effect, because the produced bipyramid already possess these other symmetry elements (they are implied). So our result is this bipyramid, the hexagonal protopyramid (= type I pyramid).

Its stereographic projection is given in (2) of Figure 6.

Figure 6. (1). Stereogram of the symmetry elements of the Dihexagonal-bipyramidal Crystal Class and of the face a : ~a : -a : c.

(2). Stereogram of the (primary) hexagonal Protopyramid, the first Form of the Class.

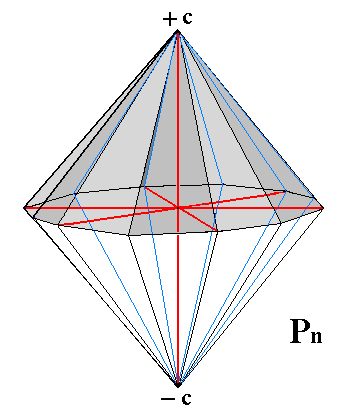

The hexagonal protopyramid itself is shown in Figure 7.

|

Figure 7. Hexagonal Protopyramid, and its orientation with respect to the four crystallographic axes. From these axes unit pieces are cut off by the upper front face. |

The Weiss symbol for this primary protopyramid is (a : ~a : -a : c), and the face a : ~a : -a : c is, besides being the unit face, also one of the basic faces of the Hexagonal Crystal System. When such a basic face is subjected to all the symmetry elements of a certain Crystal Class then one of the Forms of that Class is generated.

The Miller symbol for the protopyramid can be found as follows.

The derivation coefficients can be read off from the Weiss symbol. They are consequently

1 ~ (= infinity) 1(-) 1. Their reciprocals are 1/1 1/~ 1/1(-) 1/1. And they are equal to

1 0 1(-) 1. So the Miller symbol for this pyramid is { 101*1 }.

The Naumann symbol is P.

The next Form is the (primary) hexagonal deuteropyramid (= type II pyramid).

Although it is, like the protopyramid, a hexagonal bipyramid, it is not just a rotated protopyramid, but has a slightly different shape, it is a little bit more obtuse. I will explain why this is the case. The next Figure shows this deuteropyramid.

|

Figure 8. Hexagonal Deuteropyramid, and its orientation with respect to the four crystallographic axes (red lines). From the a3 axis a unit piece is cut off by the upper front face (the unit piece refers, with respect to its length, to the Protopyramid. |

The Weiss symbol for this (primary) deuteropyramid is (2a : 2a : -a : c). So the derivation coefficients are respectively 2 2 1(-) 1. Their reciprocals are 1/2 1/2 1/1(-) 1/1. To convert these to whole numbers we multiply each one of them by two resulting in 1 1 2(-) 2. So the Miller symbol for this Form is { 112*2 }.

The Naumann symbol is P2 (i.e. the c-intercept has unit length, expressed by the absence of any number before P, while the non-unit intercepts with respect to the horizontal axes are of length 2, expressed by the 2 after the P).

To derive the deuteropyramid from the protopyramid a rotation of the latter (by 300) is not sufficient. It is even impossible in the world of crystals, because if we just rotate the protopyramid relative to the system of crystallographic axes, namely rotating it about the c axis, then the derivation coefficient belonging to the a3 axis becomes irrational (namely half of the square root of three [1/2 (square root)3]). Let us explain this by considering Figure 7 and 8.

In Figure 7, the hexagonal primary protopyramid, OA = OB = 1 (the unit distance). If we rotate this pyramid by 300 clockwise about the vertical axis and if we imagine that we then get the pyramid of Figure 8, then OC (in Figure 8) would be equal to OB (in Figure 7), i.e. it would be 1. But then OD would be 1/2 (square root)3 (= 0.866...). See Figure 9.

|

Figure 9. Horizontal crystallographic axes and (the traces of) three faces (black) (one face and parts of two adjacent faces) of the Deuteropyramid. |

In Figure 9 the angle COL is 600.

OL = OC.

So OCL is an equilateral triangle. This implies that CD = 1/2 CL = 1/2 OC.

So if OC = 1 (= the unit distance OB in Figure 7), then (1/2)2 + (OD)2 = 12, and this is equivalent to 1/4 + (OD)2 = 1.

So (OD)2 = 3/4.

Thus OD = (square root)3 / (square root)4, which is equal to 1/2(square root)3 (= 0.866...).

Remark :From Figure 9 we can also see that KOD is half an equilateral triangle, which implies that OK = 2OD. In the same way OM = 2OD holds.

So if OD is set equal to one (i.e. equal to OB of Figure 7), in other words if OD is the unit distance (unit intercept), then OK = 2, and OM = 2, establishing the Weiss symbol for the face CL and giving (2a : 2a : -a : c) for the deuteropyramid.

This means (if OC = 1) that the coefficient for the a3 axis has become irrational. But it is proven that the derivation coefficients can never become irrational (this impossibility is a direct consequence of the periodic internal structure of crystals), and so we cannot derive the deuteropyramid from the protopyramid by just rotating the latter (300). We must enlarge the equatorial plane such that OD (in figure 8) will become equal to 1 again, and thus equal to OB (in Figure 7). So we must enlarge the equatorial plane by a linear factor of 1.1547... (because 1.1547... times 0.866... equals 1). Thus, if the intercept with respect to the c axis remains the same, then this pyramid is not congruent with the protopyramid but is a little more obtuse. When we would proportionally enlarge the c-intercept, the two pyramids still would not be congruent but they are then similar pyramids, they have the same shape, but differ in size. However in this case the deuteropyramid (with enlarged c-intercept) is not a primary deuteropyramid anymore, because of the enlargement mentioned (the distance OF in Figure 7 is the unit intercept with respect to the c axis, and the corresponding intercept in the similar deuteropyramid (where the intercept was enlarged) is longer, i.e. longer than the unit intercept for this axis).

Let's recapitulate and draw some conclusions.

A deuteropyramid is not similar to (and thus certainly not congruent with) the primary protopyramid (P) when this deuteropyramid is itself primary (P2), in which "similar" means "having exactly the same shape". But it can be made similar to the primary protopyramid by an appropriate change of length of the c-intercept, causing the deuteropyramid not to be primary anymore. And even when this deuteropyramid is now (made) similar, it still is not congruent with the primary protopyramid. So if a deuteropyramid combines with a primary protopyramid its faces must have a definite relationship to those of the protopyramid : they cannot just be anywhere in the combination, but can only occur at certain definite distances from the faces of the protopyramid with which they combine, because the deuteropyramid is not congruent with the protopyramid.

To fully understand the relationships between the hexagonal proto- and deuteropyramids, and also the relationship between them and the dihexagonal pyramid (a Form yet to be discussed), it is useful to consider the equatorial planes of those Forms (All such considerations are equally valid for all the yet to be discussed prismatic Forms, the protoprism, deuteroprism and the dihexagonal prism). See Figure 10, 11 and 12.

Figure 10. Equatorial planes of the hexagonal Protopyramid and Deuteropyramid.

When we want to derive the Deuteropyramid from the Protopyramid, we rotate the Protopyramid (red) 300 about the main crystallogaphic axis (the resulting equatorial plane is given in a greenish color) and enlarge that resulted equatorial plane till

the a1-intercept is equal to 1 again.

In the next Figure I show the relationship of the dihexagon with the hexagons (equatorial planes) of the proto- and deuteropyramids. As the hexagons are the equatorial planes of the proto- and deuteropyramids as well as of the proto- and deuteroprisms (Forms yet to be discussed), the dihexagon is the equatorial plane of the dihexagonal pyramid as well as of the dihexagonal prism (Forms yet to be discussed).

|

Figure 11. When we construct a dihexagon in the way indicated (black) we get a special dihexagon, namely a regular dodecagon, i.e. a completely regular polygon consisting of twelve equal sides and twelve equal angles (corners). This is evident from the fact that the green hexagon is just the result of the rotation of the red hexagon ( by 300 ), implying congruent triangles from which the absolute regularity is easily proved. In the next Figure we will construct a general dihexagon. |

|

Figure 12. When we construct a dihexagon in the way indicated (black) we get a general dihexagon. It is a kind of irregular dodecagon, i.e. a polygon consisting of twelve equal sides and twelve angles (corners) which are alternately the same. I.e. it has six angles of the same size, and six others, different from the first group but equal among each other. The dihexagon can vary between two extremes, the Protopyramid and the Deuteropyramid, as is evident from this and from the next Figure. |

Figure 13. Range of possible dihexagons (the general ones, but also the special (regular) case). The possible intercepts related to a representative side of the dihexagon (corresponding to a representative face of the associated Dihexagonal Pyramid or Prism) can vary between those of the Protopyramid and those of the Deuteropyramid.

In the next Figure we show the axial relationships of the general dihexagon (as the equatorial plane of the dihexagonal pyramid and prism, and as such representing those Forms).

Figure 14. Axial relationships of the sides -- representing faces -- of the general Dihexagon with the horizontal crystallographic axes of the Hexagonal Crystal System.

In Figure 14 the intercept with respect to the a1 axis is OC. The intercept with respect to the a2 axis is OE. The intercept with respect to the a3 axis is OB.

OB is equal to 1 (unit intercept).

If OE = s, then the length of OC is determined, it in fact is s / (s-1), which we will prove below See Figure 15.

Figure 15. If the intercept with respect to one axis is set to 1, and if the intercept with respect to a second axis is set to, say, s, then the intercept with respect to the third axis is determined. It is s / (s-1). (See below).

The axes a1, a2 and a3 are effecting six angles of 600 around O. (See Figure 15). So the angle COB is 600.

AB is a side of a dihexagon. It represents a face of a dihexagonal pyramid or prism.

The intercept for AB with respect to the a2 axis is OE. Let its length be s.

The intercept for AB with respect to the a1 axis is OC.

The intercept for AB with respect to the a3 axis is OB, which is (set) equal to 1 (unit distance).

Now we draw ED parallel to OC. We then get two similar triangles COB and BED.

The angle DOE = 600.

Because the angle enclosed between -a2 and +a1 is equal to 600, the angle OED is also 600 (recall that ED is parallel to OC).

It follows that now the angle EDO is also 600, and thus the triangle OED is an equilateral triangle. This means that ED = OE = s, and OD is also equal to s.

Because OB = 1, BD = s-1.

Because the triangles COB and BED are similar, the following proportions hold :

OB : BD = 1 : s-1 = OC : ED.

Because ED = s, we get :

1 : s-1 = OC : s, which can be written as

1 / (s-1) = OC / s, which is equivalent to OC = s / (s-1).

So if the intercept with respect to the a2 axis is equal to s, and the intercept with respect to the a3 axis is equal to 1, then the intercept with respect to the a1 axis (= OC) is equal to s / (s-1).

So the general Weiss symbol for a dihexagonal pyramid is

( [s/(s-1)]a : sa : -a : mc ), with the derivation coefficient for the first a equal to s / (s-1).

The derivation coefficient for the a1 axis must lie between 1 and 2.

When it would be 1 we get the protopyramid (P).

When it would be 2 we get the deuteropyramid (P2).

So when we take (for example) s = 3 and m = 1 (the latter means that the intercept with respect to the c axis has unit length), then we get ( [3/2]a : 3a : -a : c ) (and the coefficient for the first a is indeed between 1 and 2), and we could consider the face [3/2]a : 3a : -a : c as one of the basic faces for the Hexagonal Crystal System.

So we now have already found three such basic faces :

a : ~a : -a : c

2a : 2a : -a : c

[3/2]a : 3a : -a : c

We will find four more of these, and we will later use them (in our "Facial Approach") to derive the Forms of the lower symmetry Classes of the present Crystal System.

The equatorial plane of the dihexagonal pyramid is already given earlier. In the next Figure the pyramid itself is shown.

|

Figure 16. The Dihexagonal Pyramid, is a bipyramid consisting of 24 faces, each of which is an unequilateral triangle. Upper faces shaded. Also visible is the system of crystallographic axes (red). |

The Weiss symbol representing a general dihexagonal pyramid is ( [s/(s-1)]a : sa : -a : mc ), and the Naumann symbol is mPn, where n = s / (s-1). If (for example) s = 3 and m = 1, then the Miller symbol is {213*3}.

The next three Forms can be derived from the pyramids (protopyramid, deuteropyramid, dihexagonal pyramid) by making the intercept with respect to the c axis (i.e. the vertical axis) infinitely long, which means that all the faces are parallel to the c axis and thus are vertical. In this way we get respectively the protoprism, deuteroprism and dihexagonal prism.

We begin with the dihexagonal prism.

Its equatorial plane is identical to that of the dihexagonal pyramid. It is depicted in Figure 17.

|

Figure 17. The Dihexagonal Prism, is a prism consisting of 12 vertical faces. Any horizontal section of it is a same dihexagon. It is an open Form, which in this case means that it is not closed by top or bottom faces. Such a prism can however engage in a combination with another Form of this Class (yet to be discussed), namely the Basic Pinacoid, which consists of two horizontal parallel faces which could close the prism at the bottom as well as at the top. Also visible is the system of crystallographic axes (red), and their bisectors. |

The Weiss symbol for a dihexagonal prism is ( [s/(s-1)]a : sa : -a : ~c ), the Naumann symbol is ~Pn. If s = 3, then the Miller symbol is {213*0}.

With all this we have also found yet another basic face, compatible with the Hexagonal Crystal System, namely -- generally -- the face [s/s-1)]a : sa : -a : ~c. If we take s = 3, then we can take as the (newly found) basic face [3/2]a : 3a : -a : ~c.

The next Form is the hexagonal protoprism. It can be derived from the protopyramid by steepening the sides till they are vertical. It is depicted in Figure 18.

|

Figure 18. The hexagonal Protoprism, is a prism consisting of 6 vertical faces. Any horizontal section of it is a same hexagon. Like the Dihexagonal Prism it is an open Form. It too can combine with a Basic Pinacoid to close its top and its bottom. Also visible is the system of crystallographic axes (red). |

The Weiss symbol representing the protoprism is (a : ~a : -a : ~c). The Naumann symbol is ~P. The Miller symbol is {101*0}.

With it we have yet another basic face compatible with the Hexagonal Crystal System, namely the face a : ~a : -a : ~c.

The next Form is the deuteroprism. It can be derived from the deuteropyramid by steepening its sides till they are vertical. Like the protoprism any horizontal section of it is a regular hexagon. The deuteroprism is depicted in Figure 19.

|

Figure 19. The hexagonal Deuteroprism, is a prism consisting of 6 vertical faces. Any horizontal section of it is a same hexagon. Like the Dihexagonal Prism and the Protoprism it is an open Form. It too can combine with a Basic Pinacoid to close its top and its bottom. Also visible is the system of crystallographic axes (red) and their bissectors. |

The Weiss symbol for the deuteroprism is (2a : 2a : -a : ~c), and its Naumann symbol is ~P2. Its Miller symbol is {112*0}.

With all this we have found yet another basic face compatible with the Hexagonal Crystal System, namely the face 2a : 2a : -a : ~c.

The last Form to be discussed is the basic pinacoid. It consists of two faces, parallel to each other and to the equatorial plane of the system of crystallographic axes. This Form is, like the prisms, an open Form, it can only occur in combinations which result in closed Forms, as is the case when a prism is closed at its bottom and at its top by this pinacoid. The basic pinacoid is depicted in Figure 20.

|

Figure 20. The hexagonal Basic Pinacoid, is a Form consisting of 2 horizontal faces. The system of crystallographic axes (red) is also shown. |

The Weiss symbol for the hexagonal basic pinacoid is (~a : ~a : ~a : c). The Naumann symbol is 0P, and the Miller symbol is {0001}.

With all this we've also found the seventh and last basic face compatible with the Hexagonal Crystal System, namely the face ~a : ~a : ~a : c.

All these Forms can engage in combinations with each other in real crystals.

This concludes our exposition of the Dihexagonal-bipyramidal Crystal Class.

Besides (and correlated with) the Forms of this Class we found the following seven basic faces compatible with the Hexagonal Crystal System :

a : ~a : -a : c

2a : 2a : -a : c

[3/2]a : 3a : -a : c

[3/2]a : 3a : -a : ~c

a : ~a : -a : ~c

2a : 2a : -a : ~c

~a : ~a : ~a : c

As has been said, we'll use these basic faces to derive (in one out of two approaches) the Forms of the lower symmetrical Classes of the Hexagonal Crystal System.

To continue, klick HERE for Part Two (Class 6 m m).